Pine Mountain Settlement School

DANCING IN THE CABBAGE PATCH V

FARM & DAIRY I – EARLY YEARS 1913-1930

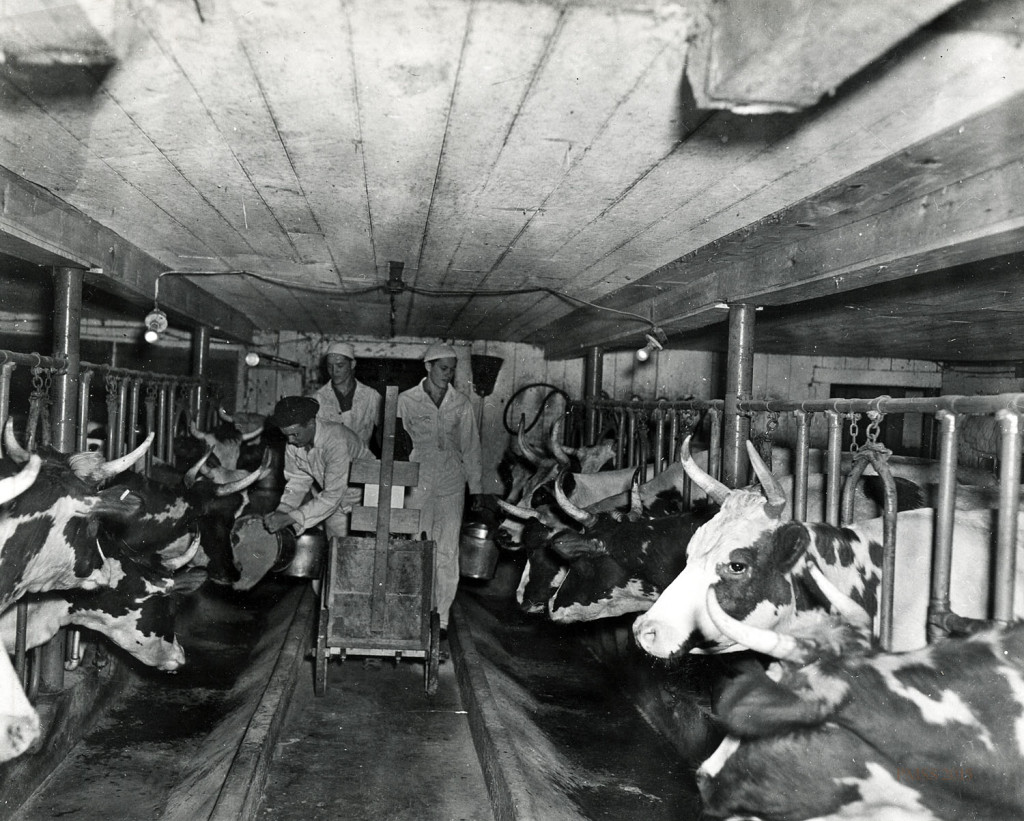

Katherine Pettit imagined that one of the most beneficial programs at the school would be a herd of cows to supply milk, cream and butter for the school.

Barn. View of flank. Constructed in 1915.

With the assistance of Philip Roettinger, a Trustee from Cincinnati, who raised $500 dollars, a barn was constructed in 1915 and some so-called “mountain-scrub” cows were purchased as a starter herd. These were largely Guernsey’s. But, in 1916 an attempt was made to be more selective regarding the breed of cow and four cows and a bull were purchased for the school.

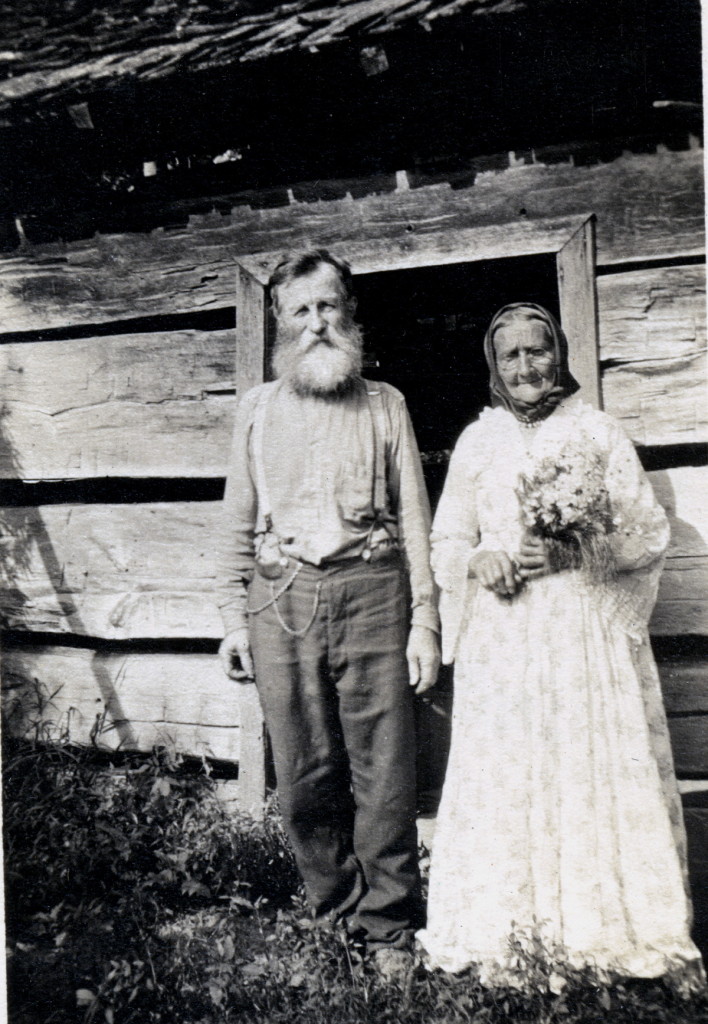

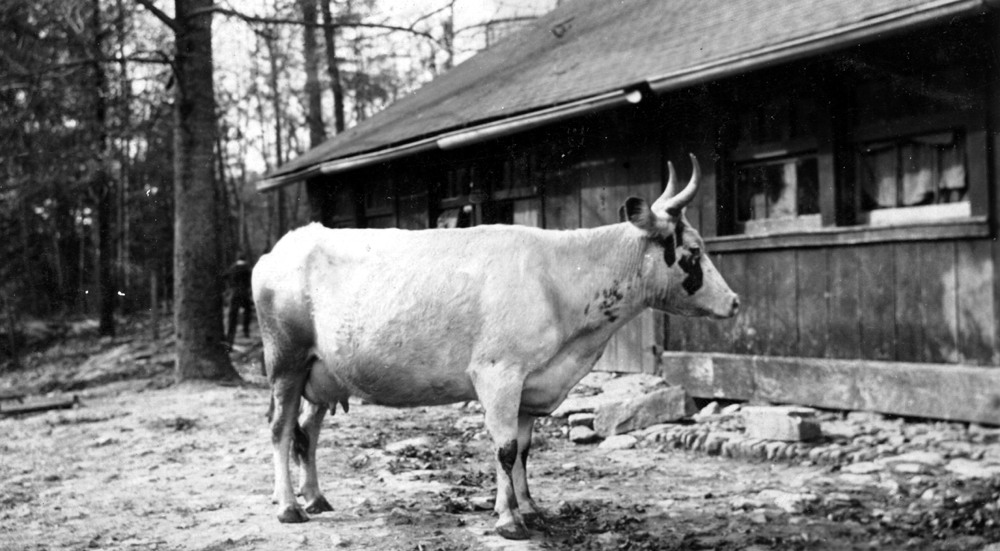

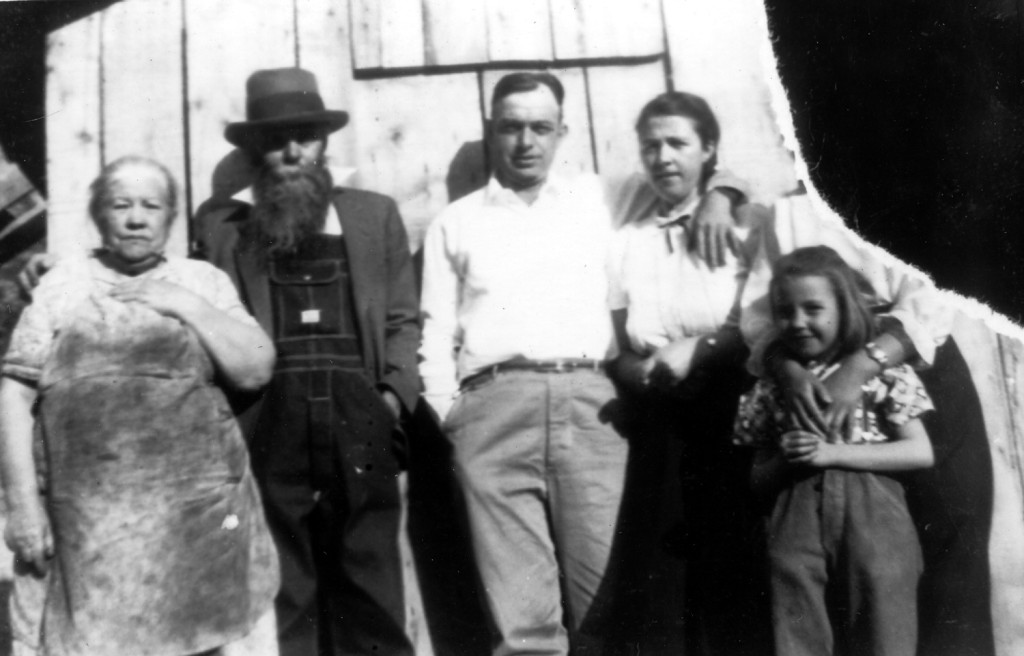

Mrs. Burns, farm manager and friend (?) and one of the “scrub” cows first milked at the School. New barn, behind.

This early breed was not satisfactory in the environment and by 1920 the school had shifted to two Holsteins and a bull. This breed also proved to not be satisfactory and Pettit then consulted with the Kentucky Experimental Station at Quicksand and with the Harlan County Extension agent, Mr. Robert Harrison. They both believed the Ayrshire breed might be best suited to the mountainous area and to the school needs. While the school sorted out the cow problems, they maintained a mixed herd of Jerseys Holsteins and Ayrshires.

Miss Elizabeth C. Hench, also a Board member, was the leader in the campaign for the development of the Ayrshire herd and her correspondence and fund-raising efforts comprise some of the most amusing and creative fund-raising campaigns the school has ever mounted.

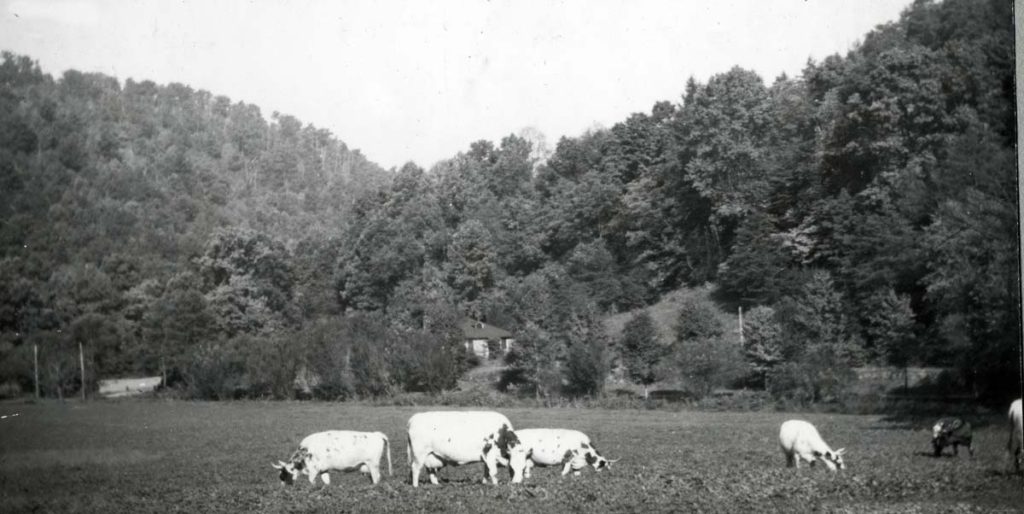

Ayrshire cows in field, Office in background. [nace_II_album_043.jpg]

AYRSHIRES – THE JOYFUL HERD

The Joy Stock Company, Limited, came to Pine Mountain in 1921 with two heifers, Joy and Delight. The third heifer, Joyce, arrived in August 1927. While the backside of this cow may not look so joyful, the arrival of Joyce on August 9, 1927, was both a joyous and a be-deviling occasion. The bovines did not come in mass, but in increments as they could be afforded. The Joy Stock Company and Ruth [Elizabeth] Hench, secretary of the Board of Trustees, were the force behind the practice of dairying at the School. For years Miss Hench maintained a lively correspondence with donors to grow the herd and to keep the herd fed.

The arrival of the third Ayrshire, Cavalier’s Ruth III, familiarly known as “Joyce”, is described by Miss Hench and by the Assistant Director, Mrs. Zande in a series of delightful exchanges.

“JOYCE, THE NEW AYRSHIRE HEIFER, arrived at Pine Mountain on the afternoon of August 9. She was purchased at the Spring City Stock farm of Waukesha, Wisconsin. She is a registered heifer due to calf about October 10. The sire of this heifer is among the best of the breed, and her dam produced 12,007

pounds of milk in 300 days, milking as high as 82 pounds per day. Her registered name is, Cavalier’s Ruth III, but her nickname at Pine Mountain is’ Joyce’.”

Mrs. Zande responded to Miss Hench’s new purchase:

“Your letter reminds me of a phrase Dr. Osler used over and over in his life —— ‘The angel troubling the pool”.

Miss Hench continued,

“Joyce has temperament and horns. She didn’t enjoy her train trip from Wisconsin (and she came EXPRESS), “refused to be led over the mountain peacefully from Putney, six men could do nothing with her, and she was finally crated up again and brought over in the log train. Brit Wilder, Uncle William’s grandson, and Mr. Browning, the farmer, were both in attendance. A large reception committee awaited her Tuesday but like all famous people she disappointed us and arrived later than she was scheduled.”

Miss Hench replied to Mrs. Zande’s concerns that not enough study had been given to the raising of cows:

DEAR MILK-GIVERS …

” So, one week-end at Berea, I borrowed four text books from the professor of cowology and immersed myself in the subject. I learned that the Ayrshire cow hails from Bobbie Burns’ shire, which lies two thousand feet above sea—level where the winters are cold. In 1800 the farmers began to improve their wild stock by cross—breeding. Now, whether for hillside climbing or nibbling short grass, the Ayrshire leads all breeds of dairy cows. They are largely white, brindled with color from deep red, seal brown, to a clear cherry red. Like the Scotch owners they are sometimes headstrong, forceful, and willing to assert themselves. But they have long graceful horns and they are stylish in appearance. The milk is not as abundant as that of the Holstein, nor as rich in butterfat as that of the Jersey arid Guernsey, but they are suited to conditions at Pine Mountain. So, if I have troubled the pool, I hope I have quieted the wavelets.”

Miss Pettit responded in her typical diplomatic style:

“We are so grateful to the Joy Stock Company…. I have always wanted you to know how thankful I am for the intelligent interest of all of you in this most important department…When Mrs. [Martha] Burns, the dairy woman, returns, she will win Joyce’s heart by her gentleness, kindness, and care.”

The Ayrshires stayed and multiplied.

The Ayrshire herd grazing at the knoll. Arthur W. Dodd Album. [dodd_A_009_mod.jpg]

Miss Hench reports in 1929:

“Dear Milk-Givers:

54 thrills were what I had in 1928 from the gifts to the Joy Stock Company, Limited.

1928 . . . …. $320.10

Grand total …. $2474.00

Joyce had 1098 meals, three extra ones on February 29. She, being a cow, ruminated but did not thrill.

There are no marathons in our barn yard. So this is a fitting time to reproduce a letter used 6 years ago, a letter often asked for. It is a bona fida production of a Kentucky mountaineer:

‘Dear sir

I got your letter asken for a list of my assets and liabilities now i told you wen i sent in that order that i was keeping a restarent and not a general store and i dont keep such things as assets and liabilities on hand and besides if i did it aint none of your dam bisiness how much monie have i got no how. They was a feller noseing around here yesterday wot said as how his name was r g dun & companie and he asked me how much money did i have and i kicked him clear into the middle of next Sunday. i tell you i wont have no meddlin in my business i am as good as any man and a dam site bettern som if you dont want to sell me them goods wy go to hell. please answer by next mail.

Your fren, jake’

Miss Hench writes:

“My books are open to your inspection. Joyce’s board is paid knee-deep in June. Her new calf is named Rejoice. As our cow is doing her best, I know we shall match her endeavor.

From one who is no coward,

Elizabeth”

The herd continued to grow and when Joyce’s third calf was born it was named ‘Overjoy’ to which Hench replied, “When that series of names is exhausted, what next?”

Even during the Great Depression of the 30s the supporters of the Joy Stock Co. were generous. Miss Hench’s appeal to donors while clever and light, was not without reflection on the serious economic conditions in the country.

From Miss Hench to her donors:

Financial Center January, 1931

Dear Heirs and Assigns of the Original Cow Company:

44 stockholders during 1930 A.D. (Acute Depression) contributed $275.00 to the support of Joyce at the Pine Mountain Settlement School. That brings the grand total since 1920 up to $3027. I thank you all, the —whole company of 124 strong.

… Some of you have received notice that your contributions would be applied to a new Milk Boom at the Barn, I have $189.05 for that fund. When winter comes and the boys cannot work out of doors, then, under the direction of the Woodworking teacher (a former Pine Mountain boy) and the new Danish farmer, we shall enlarge one room of the Barn, install a stove, a hot water tank, and a sink in which to scald the buckets and pans. We shall have also a cooling machine to make our milk bacteria free by dropping it to 34 degrees within an hour after milking it.

A happy New Year to all of you and the wish that 1931 may mean the return of the good old times.

Elizabeth

Barn. Ayrshire cow. [II_7_barn_285.jpg]

January, 1932

Dear Partner in our kine undertakings:

During the year 1931 people became acquainted with a new phrase – new low level. But this was not true of the Joy Stock Company, Limited. We received $200, better by several dollars than our early holdings.

Since we are in the cow business, we must look to cows for our theme. It is quiet contentment. In the past, our ancestors, always cow owners, evolved two proverbs:

(l) Contented is the heart that thinks like a cow.

(2) It is a bawling cow that misses its calf the least.”

In a recent novel by a popular Scotch author there is this significant passage:

“No, I am not a pessimist. But I haven’t been through bad enough times to justify me in being an optimist. . . To declare oneself an optimist, without having been down into the pit and out on the other side, looks rather like bragging.”

So it becomes us to be quiet, even if we cannot be contented.

I saw our cows in October when I went to the Pine Mountain Settlement School for the biennial meeting of the Board of Trustees. You will be sorry to learn that we have heard the last bellow of Joyce. I gave a check to cover her board through December 31, 1931. After that we shall forget her and feed our new cow, REJOICE, whom we bought October 26th for $150, plus hauling $25. =$175. She is a fine big Ayrshire and I am certain you would love her too. It is now up to you and to me to see that she has daily food. As all four of her stomachs are larger than those of Joy, Delight, and Joyce, she will therefore require more food and hay.

Your friend who usually has a cow in tow,

Elizabeth

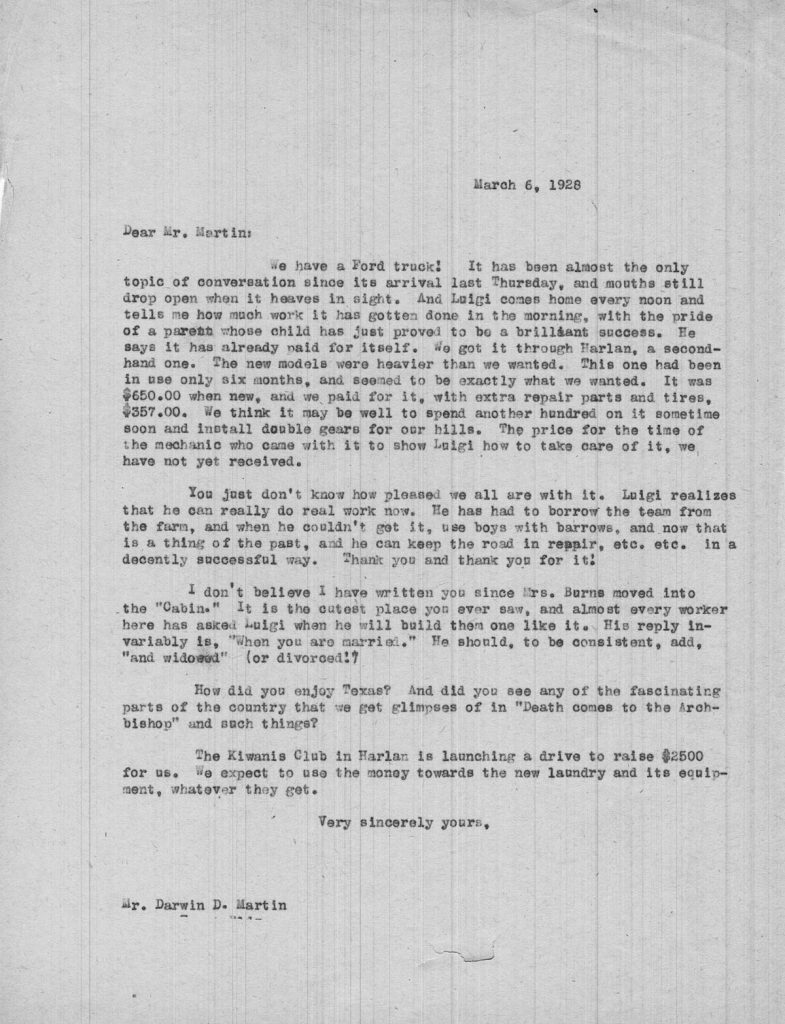

Another addition to the farm came in 1928 when the school was able to purchase a second-hand truck. With funding secured by Darwin D. Martin, Chairman of the Board of Trustees in 1928 the school was now able to be more efficient with many tasks. Ethel de Long Zande wrote to Martin to thank him for the gift and said:

[IMAGE: Copy of letter ] Left: Letter from Ethel de Long Zande to Darwin D. Martin, (March 6, 1928) thanking him for his help in securing a much-needed truck for the farm.]

Darwin D. Martin was a Vice President of Larkin & Co., a catalog order company centered in Buffalo, New York. Martin served on the Pine Mountain Board of Trustees through most of the late 1920s and was an active supporter of the School and its programs, contributing consultation and many items of critical importance for operation.

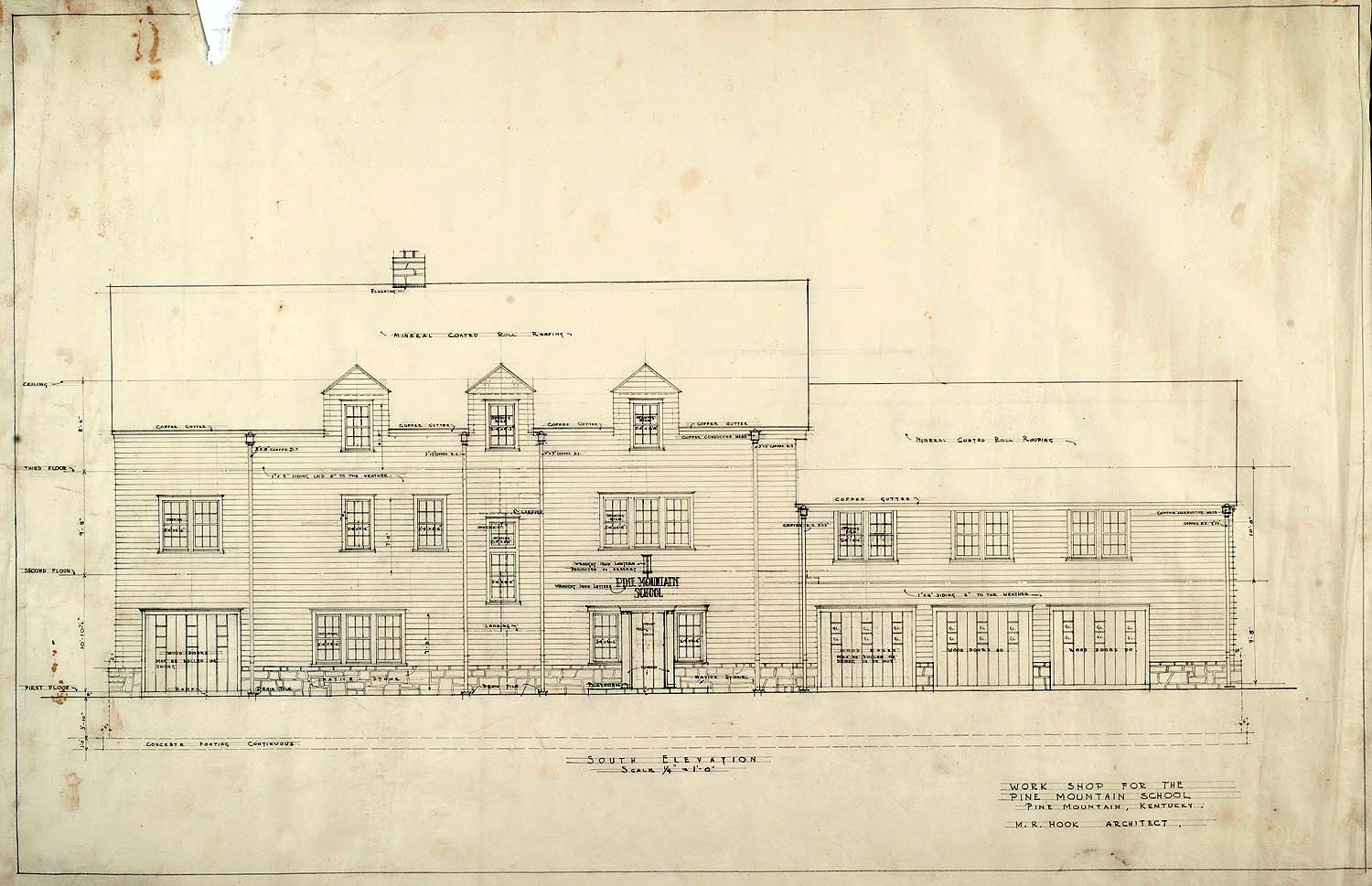

Martin was one of the wealthiest executives in the country in the 1920s, and the primary benefactor for the architect Frank Lloyd Wright. Personally responsible for financial support of nearly 15 of Wright’s building projects, mainly Taliesin, he had Wright design his own Martin family complex in Buffalo in 1902-1909. A difficult childhood prompted him to gather his family around him in a series of homes. The complex is one of the most outstanding examples of Frank Lloyd Wright’s “Prairie Style” architecture.

While there is no evidence that Martin had his hand in the architectural planning of Pine Mountain, his connections were available to Mary Rockwell Hook, Pine Mountain’s architect. As his health deteriorated in the late 1920s Martin resigned the Board. He died in 1935 following the loss of his fortune in the Crash of 1932.

March 6, 1926

[Ethel de Long Zande writes to Miss Frances Lavender, a former worker, living in Pasadena, California. and provides further details on the truck.]

“We have a Ford truck! It has been about the only topic of conversation since its arrival last Thursday, and mouths still drop open when it heaves in sight. And Luigi comes home every noon and tells me how much more it has gotten done in the mornlng, with the pride of a parent whose child has just proven to be a brilliant success. He says it has already paid for itself. We got it through Harlan, a second-hand one. The new models were heavier than we wanted. This one had been

in use only six months, and seemed to be exactly what we wanted. It was $65O.OO when new, and we paid for it with extra repair parts and tires, $357.OO. We think it may be well to spend another hundred on it some time soon and install double gears for our hills. The price for the time of the mechanic who came with it to show Luigi how to take care of it, we have not yet received. , ,”

As indicated in the letter, this truck was a critical piece of equipment for the school allowing the farm to operate without mules and horses for many operations. Further, it allowed for the transport of materials across the new Laden Trail road from the near-by town of Harlan.

Ford Truck donated by Darwin D. Martin. cobb_alice_012

[IMAGE: Truck and workers in front of the Tool Shed, c. 1926]

Ethel de Long Zande only lived two years beyond 1926. By April of 1928 she was dead after a courageous battle with breast cancer. True to her character, she worked until the last weeks of her illness.

[IMAGE: Ethel de Long Zande and her companion dog.]

In the obituary notice prepared by Evelyn Wells that appeared in the New York Times, April 5, 1928, the following is excerpted:

“…On the day of Mrs. Zande’s funeral, daffodils she had planted were in bloom in the Pine Mountain valley, but snow on the heights did not keep her friends, old and young, some with babes in arms, from crossing steep trails to honor her. …. She was laid to rest on a little rise of ground where the view encompasses the valley she loved.

In this day, when so many of those who have had large opportunities are increasingly crowding into the great urban centers to use their gifts, it is well that we pause and pay tribute to this woman of rare talents, who rejoiced in devoting them to an under-privileged people in a remote mountain section.”

The following tribute from Philippians 4:8, is on an engraved plaque in the Pine Mountain chapel.

“… whatever things are true,

whatever things are honest,

whatever things are just,

whatever things are pure,

whatever things are lovely,

whatever things are of good report;

if there be any virtue, and if there be any praise,

think on these things.”

Following the death of Ethel de Long, Miss Angela Melville was appointed interim Co-Director with Katherine Pettit. Meville served from 1928 to 1930. Like her predecessors, she was a strong supporter of the dairy farm but unlike Katherine Pettit she rarely engaged the day-to-day, Her expertise resided not in her humor or her hands-on, but in her understanding of farming and economics.

On July 20, 1928, a printed notice from the Pine Mountain Settlement School announced that the School’s board of trustees had, on April 29 of that year,

” … invited Miss Angela Melville to become associate director of Pine Mountain Settlement School, beginning August 1, assuming sole charge of the academic department and of the office and fiscal promotion of the school, all of which had the devoted care of the late Mrs. Ethel deLong Zande.”

Miss Melville was equal in authority with then director, Katherine Pettit (1913 – 1930), but with the specific areas of responsibility listed in the announcement.

Miss Melville had come from the Cooperative Bureau for Women Teachers in New York, where she had been director for the previous three years. Before that, she worked for two years with the National Credit Union Extension Bureau, organizing both industrial and rural credit unions in many U.S. states.

She had also worked a short time with the Brasstown Savings and Loan Association in North Carolina, and came highly recommended by Marguerite Butler who wrote of her in her article “The Brasstown Savings and Loan Association” in the July 1926 issue of Mountain Life & Work (vol. 2, no. 2, page 42).

She believed in the credit union, and having lived as a member of our community for several months, believed in the success of one here. Not only were every one of us filled with her enthusiasm and interest, but also made to realize the duties, responsibilities and detail of work involved in such an association.

Before Miss Melville’s appointment as associate director of PMSS, she had an earlier connection with the School. From 1916 to 1920, she organized the office and as a speaker raised funds for the School’s endowment which supported the School programs, including the farm and the Line Fork Settlement and Big Laurel Medical Settlement.

According to Darwin D. Martin, President of the Board, in the same announcement:

“Her admiration for Uncle William Creech, the founder of the school, her intimacy with its ideals, her acquaintance with you, our friends outside the mountains, and her knowledge and love of the mountains themselves, have all helped to fit her for her work here and make her the unanimous choice of the Board of Trustees.”

GO TO:

DANCING IN THE CABBAGE PATCH – ABOUT

DANCING IN THE CABBAGE PATCH I – GUIDE

DANCING IN THE CABBAGE PATCH II – INTRODUCTION

DANCING IN THE CABBAGE PATCH III – PLACE

DANCING IN THE CABBAGE PATCH IV – FARMING THE LAND 1913-1930

DANCING IN THE CABBAGE PATCH V – FARM & DAIRY I – EARLY YEARS

DANCING IN THE CABBAGE PATCH V – FARM & DAIRY II – MORRIS yEARS

DANCING IN THE CABBAGE PATCH VI – POULTRY

DANCING IN THE CABBAGE PATCH VII- IN THE GARDEN

DANCING IN THE CABBAGE PATCH VIII – IN THE KITCHEN

DANCING IN THE CABBAGE PATCH IX – DIETICIANS

DANCING IN THE CABBAGE PATCH X – IN THE DINING ROOM, MANNERS & ETIQUITTE

![Boy's House Wassailers and Lords and Ladies -- 1946. [Good King Wenselaus ?] [In Laurel House] nace_1_025b.jpg](https://pinemountainsettlement.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/nace_1_025b-1024x573.jpg)

![Angela Melville Album II - Part III. "E.K.W." [with dulcimer]. [melv_II_album_313.jpg]](https://pinemountainsettlement.net/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/melv_II_album_313-194x300.jpg)