Pine Mountain Settlement School

POST: DANCING IN THE CABBAGE PATCH

Big Trees and Big Ideas

EARTH DAY April 22, 2021

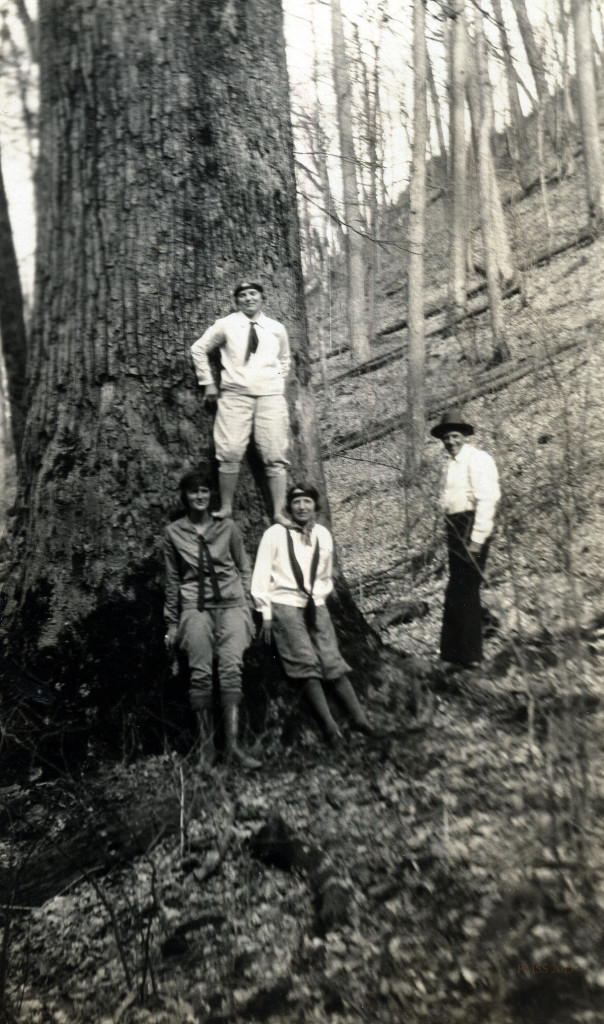

“Emily Hill, Florence Daniels, ? Wolf, Columbus Creech.” [kingman_069c.jpg] At the base of a large poplar tree at Pine Mountain Settlement, c. 1920. Emily Hill “standing” on the shoulders of 2 classmates. Columbus Creech to the right. [X_100_workers_2538_mod.jpg]

TAGS: Emily Hill, Columbus Creech, trees, Katherine Pettit, Leon Deschamps, forest ecology, old growth forests, William Tye, poetry, edge habitats, logging, preservation, timber inventories, land dispossession, Steven Stoll, Lucy Braun, oak trees, Perfect Acre, edge habitats, Speculation Land Company, Tench Coxe, William Morris, North Carolina

BIG TREES AND BIG IDEAS

THE SOVEREIGN TREES

It is difficult to ignore a tree at Pine Mountain. Like many students, they have personalities and carry memories and there are so many of them! Early on, like great sovereigns, they filled the Pine Muntain valley with fragile green in Spring and a brilliant dance of color in Fall. They still do. The giants are remembered as favorite courting markers, their roots a resting place for an outdoor barber, their leaves an endless work task, and their trunk’s loud fall to earth a cause for awe and fear. Walking into the Pine Mountain forest is almost always a topic of excitement and sometimes a poem, or, possibly a reminder of how much we have in common with trees.

In summer, the mountain’s trees are clothed in varying shades of green, but in winter, they stand naked with branches scattering on the forest floor as winter and wind prunes the fragile growth and give more life to firm but bare limbs. Unclothed, they tower, no longer umbrellas, but towering skeletons sleeping silent and majestic in their quiet forest — their roots tucked in the leaf-socks they knitted with Autumn’s wind.

When students at Pine Mountain were asked to compose essays or poems in their English classes or to write a scientific analysis, trees often figured into their creative language. For example, this poem by Pine Mountain School 1940’s student William Tye found its way onto the pages of the regional publication, Mountain Life and Work in the Spring of 1947.

TREES

All about me stately oak trees

Send their sprawling branches upward:

Sovereign they stand

O’er trees about them.

Yet drab they look, standing leafless,

While other trees

Of less dimension

Proudly display their Easter garments.

But their assets are but folly:

For these trees which now so gaily

Show forth their beauty

And rejoice in their appearance —

Theirs shall be the destruction.

They shall but feed the soil

On which the oak tree thrives,

While waxing mightier

By their destruction

The oak tree stands

Sovereign still.

William Tye. Mountain Life and Work, Spring 1947, p. 12.

“The Big Trees,” view. 06 [braun_lucy_trees013.jpg]

EARLY SETTLERS

Trees often carry our national history. When the European settlers came to America in the late 16th Century, our ancestors left countries that had waged war against their trees as their populations grew into the surrounding forests. The Native Americans, on the other hand, had a well-established and comfortable history born of respect for their surrounding forests. William Cronan, in his informative discussion of the changes that occurred in the land when the colonists arrived, tells it this way

“… the edge habitats once maintained by Indian fires tended to return to forest as Indian populations declined. but edge environments were also modified or reduced — and on a much larger scale — by clearing, an activity to which English settlers, with their fixed property boundaries, devoted far more concentrated attention than had the Indians. Whether edges became forests or fields, the eventual consequences were the same: to reduce — or sometimes, as with European livestock, to replace — the animal populations that had once inhabited them. The disappearance of deer, turkey, and other animals thus betokened not merely a new hunting economy but a new forest ecology as well. “

Cronon, William. Changes to the Land: Indians, Colonists, and the Ecology of New England, New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 1983, 2003, p. 108.

Katherine Pettit, one of the founders of Pine Mountain Settlement School, and a re-born colonist and a die-hard Colonial Dame, aspired to — or, perhaps she imagined herself to be following in the footsteps of her European ancestors — sovereigns of another sort. Pettit may never have composed a poem to a tree (I would love to find one!), and she had a somewhat tenuous relationship to the surrounding forest. I say, “somewhat,” because she had both enormous respect for trees while she warily “politicked” for her School. Her early Settlement activity was designed to continue to encourage donations from the growing timber and mining industries, as she surveyed the large demand for building material to bring her School to reality. To many, who still seek to understand her, she remains a walking conservation enigma, especially in her early years at Pine Mountain Settlement. But, there are signals that her affection for trees ran deep.

When Pettit arrived at Pine Mountain and saw the surrounding forest, her reports indicate she was enchanted with the woodland site — and she was appalled. Giant chestnut trees were still in abundance, but dying from the new Chestnut blight that was sweeping the Eastern forests. Daily trees were being hauled up the Incline railway and through her new Schoo and then over the Pine Mountain to be milled for lumber. The mighty oaks were not yet being harvested in great numbers for the barrel staves of Blue Grass liquor, but timber for mine roofing supports was picking up, and swathes of timber were being negotiated away the steep slopes of the Pine Mountain and the enormous Black Mountain. Land was rapidly changing hands and not all of the transactions were kind to the land. Along with any sale or transfer of land that could be negotiated, timber always played a large negotiating role.

Yet, many who lived on their land in the Pine Mountain valley and hollows often had a closer relationship to the land and its trees. Conservation of their trees sometimes meant survival. Maples were being regularly tapped for maple syrup, and nutswere gathered for winter fare. Fences kept wild hogs from precious gardens. But all the Pine Mountain community and the School had a more sensitive investment in their utilization of the surrounding forests.

Katherine was felling giant poplars to build her new School buildings. Bark was stripped to make baskets to carry produce, and more. Buildings needed furniture and cherry, walnut, and maple were wonderful woods to shape into desks, tables, chests, beds, and other furniture needed by the School. The modest cabins in the hollows and along the stream banks also made simpler furniture, but furniture critical for basic living needs. On the Northside of the long Pine Mountain, there was evidence of gigantic poplar trees felled to build both small and large cabins. But those very early cabins had begun to melt into the damp rural countryside by Pettit’s time. One cabin was resurrected and moved to campus. The first cabin home of Uncle William Creech was eventually moved to campus to save it from melting into the forest floor and continues to charm one corner of the School’s campus. Timber use can both charm and appall newcomers to the valley.

[Aunt Sal’s Cabin]. c. 1940s?. [nace_1_078d.jpg]

The use of trees by the Community and the School often showed marvels of ingenuity and destruction. Hickory bark was being pulled from young hickory trees to provide bottoms for chairs, baskets, and tilt-top tables. White oak shakes (shingles) were still being reeved with hand tools for the roofs of cabins. Long rows of paling fences were now ringing the property of many neighbors to the School. Some trees were being planted and others were strategically removed throughout the new School site but the nearby hills were increasingly barren and eroding as trees were sometimes removed all the way to the crest of the mountain. Under Pettit’s supervision, trees began to be managed and monitored.

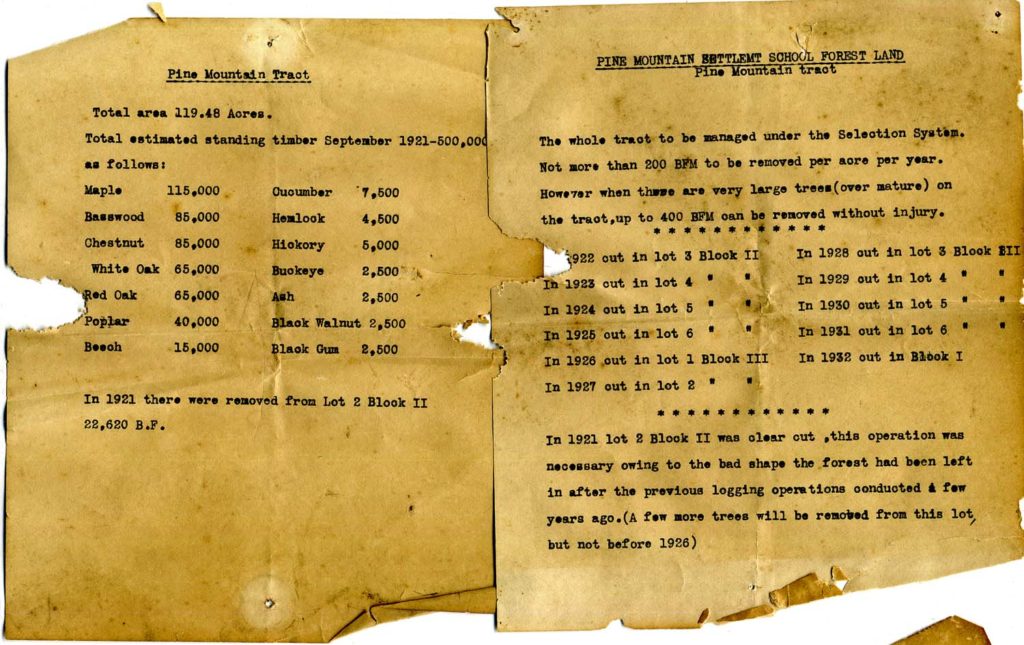

PINE MOUNTAIN SETTLEMENT SCHOOL TIMBER TRACT INVENTORY 1921

Forest management was monitored by Pettit and managed by her farmers and her new forester, Leon Deschamps. One of the earliest inventories of the timber tracts at Pine Mountain Settlement was completed c. 1921 by Deschamps, a native Belgian and the forester hired by Pettit and her staff to oversee both the forest and the farm at the School through the early 1920s. What the Deschamp inventory shows is a healthy forest on the 119.48-acre inventoried tract. The School forest was a forest comprised of the standard timber resources of the day: maple, basswood, chestnut, white oak, red oak, poplar, beech, cucumber, hemlock, hickory, buckeye, ash, black walnut, black gum, in the amounts indicated below

| Maple | 115,000 | Cucumber | 7,500 |

| Basswood | 85,000 | Hemlock | 4,500 |

| Chestnut | 85,000 | hickory | 5,00 |

| White Oak | 65,000 | Buckeye | 2,500 |

| Red Oak | 65,000 | Ash | 2,500 |

| Poplar | 40,000 | Black Walnut | 2,500 |

| Beech | 15,000 | Black Gum | 2,500 |

Deschamps advised Pettit that not more than 200 Board Foot Measurement (BFM) were to be removed per acre per year and further advised that if there were large trees on the acre (what he described as “over mature”) that up to 400 BFM “could be removed without injury.”

Deschamps then provided a ten-year plan for management that included the lot to be cut and the Block (I, II, III). He adds

In 1921 lot 2 Block II was clear cut, this operation was necessary owing to the bad shape the forest had been left in after the previous logging operations conducted a few years ago. (A few more trees will be removed from this lot but not before 1926).

Land Use Timber and Logging Record 1921, Pine Mountain Settlement School Collections, p. 2

LEON DESCHAMPS AND THE “PERFECT ACRE”

Deschamp’s Perfect Acre, as of May 2016. pmss_archives_perfect_acre_2016]

During his years as the forester at Pine Mountain, Leon Deschamps created what he called the “ Perfect Acre.” It was a small demonstration plot just behind the Chapel at the School. Today it bears little resemblance to Deschamp’s original plot as many of the trees have been removed when they overgrew the perimeter of the Chapel roof. The older trees created complex moisture issues for the backside of the Chapel and the potential for roof damage due to falling limbs, and the nearby trees were “weeded out” of the Perfect Acre. It is difficult to know how Deschamps would have felt about this “weeding”. Today, the view out the back windows of the Chapel still charms the viewers.

In a letter from Pettit to Leon Deschamps. Just three years after the creation of the plot and after Deschamps had left the employee of the School, Pettit was fretting about the special acre. Without the watchful eye of Deschamps, the little plot was causing concern. Miss Pettit wrote a letter and, with her usual demanding tone, asked Deschamp to give her some direction. Leon Deschamps had left the School in 1923 following his marriage to May Ritchie, one of the famous Singing Family of the Cumberlands Ritchies. The Deschamps couple had moved to John C. Campbell Folk School in North Carolina, where Leon had assumed a variety of responsibilities, including farmer, forester, and architect. Pettit’s letter pleads for guidance in dealing with the weeds on the “perfect acre ” site.

July 2, 1928

Dear Mr. Deschamps:

You remember you told me never to go into the Perfect Acre, and do one single thing unless you told me to. There is so much underbrush now, especially ironweed, that I believe something ought to be done about it. We have done a pretty good job getting rid of the ironweed on this place, and are at work now on dock and ragweed.

When I asked Mr. Browning if he could give a day’s work to getting the ironweed out of the perfect acre, he reminded me again of your orders. Now, if you have any further directions, please tell me. …

See: Leon Deschamps “The Perfect Acre”

We don’t have Leon Deschamp’s answer to Pettit, but he certainly had recommendations.

While the charm of the view out the back windows of the Chapel continues to be beautiful, and we don’t have the privilege of knowing what Deschamps replied to Pettit, nor have we photographs of the early “Perfect Acre”, the remnants of the perfect plot are still there. The anxious question from Pettit signals how rapidly the forest and the field can overtake the land and the vigilance needed to maintain the acreage at the Pine Mountain Settlement. Conservation became a point of concern for Pettit until her death. An image of the plot today can be seen below.

KATHERINE PETTIT AND EMMA LUCY BRAUN

What we can discern from the brief letter exchanges we have gathered regarding the “Perfect Acre” is that Deschamp, the forester, and William Tye, the poet, were both passionate about trees, and that Pettit was a responsible and respectful steward. We also know that Katherine Pettit seems to have grown into her environmental conscience, for at the end of her lif,e she became a vocal and energetic defender of trees. Her end-of-life advocacy for stands of virgin timber in Eastern Kentucky is well documented. She joined forces with her friend, the well-known environmentalist Emma Lucy Braun, to save the dwindling ‘big trees” of the area. Through Pettit’s efforts and those of Lucy Braun and others, many of the finest stands of timber and the largest trees in Kentucky forests may be found in the southeastern counties of Kentucky. For example, Pine Mountain has the tallest hemlock in the State. (See page Big Trees.) And Lilly Woods has the largest tract of old-growth forest in the State.

THE SCRAMBLE FOR APPALACHIA

“Looking East P.M.S. School: Model Home, Infirmary, Office, Logging Train or Dinky. 4.” [norton_015.jpg]

During the first two decades of Pine Mountain Settlement School, there were other forces at work in the forests at Pine Mountain. These forces had started their push against nature much earlier. Many of these depredations are still at work. Author Steven Stoll, in his landmark study of the ecological dispossession of the Southern Appalachian mountains, traced several paths that he and others believe led to massive take-downs of virgin forests across the region. His book, Ramp Hollow: The Ordeal of Appalachia, (2018) is focused on western Pennsylvania and on West Virginia, but his observations encompass the Central Appalachians and call attention to threats that continue to emerge in the forests of the region.

By tracing the history of the Appalachian region from the seventeenth century to the twentieth, and by exploring the idea of the history of *enclosure as a part of the history of capitalism in the region, Stoll leads his readers on a worrisome journey. It’s a journey from the early Colonial exploitation of forests to the later clear-cutting and destruction of the Appalachian forests. In his well-written exploration of the subject, he highlights the ravages of clear-cutting.

In his well-written book, Stoll specifically explores the eventual dependency of many mountain households on the ecological base of the surrounding forests, and he ties that cultural relationship and its ecological threads to later practices of timber harvest. It is the interwoven practices of poor timber stewardship and no timber stewardship that he contends contribute to the ongoing saga of what he calls destructive dispossession. It is a dispossession not unlike that which happened with coal.

This mercenary scramble for Appalachia, as described by Stol,l is compelling.

… An army could invade [Appalachia] but never dominate the mountains. Capital moved differently. It acted through individuals and institutions. It employed impersonal laws and the language of progress. Mountain people knew how to soldier and hunt, to track an animal or an enemy through the woods. But few of them could organize against an act of the legislature or to stop a clear-cut. The scramble built upon these vulnerabilities, but it did not happen all at once. The first thing it required was a conversion in the ownership and uses of the land.

Stoll, Steven. Ramp Hollow: The Ordeal of Appalachia, New York: Farrer and Strause, 2017, p.130-131.

DISPOSSESSION HISTORY

The conversion to dispossession came early in the Appalachian mountains in the form of land grants and very early purchases by wealthy speculators. These early mountain real estate “deals” are still being fought over and litigated. While much of the race to own land as a form of capital was quite early, the sale and resale and poor record tracking resulted in decades of litigation. A classic example of the practice of land speculation can be found in the so-called Speculation Lands tracts owned by Tench Coxe, his partners, and successors in the state of North Carolina. The Coxe empire that spread throughout Western North Carolina and eventually encompassed over 144,000 acres sheds considerable light on the questionable race to “dis-posses” by any and all means. Records from the large Speculation Lands Company are held by the University of North Carolina at Asheville, Appalachian State, and Chapel Hill, and together they represent an instructive example of the “dispossession” process.

Tench Coxe (May 22, 1755 – July 17, 1824) was an American political economist and a delegate for Pennsylvania to the Continental Congress in 1788–1789. His skills at dispossession were well known during his lifetime. It is telling that he was known to his political opponents as “Mr. Facing Bothways.” As assistant to Alexander Hamilton, the Secretary of the Treasury under George Washington, Coxe was an “insider.” He was also no newcomer to the personal monetizing of land holdings. The cycle of his speculation centered on timber and minerals and strategies to dispossess as many landholders as possible in the far reaches of western North Carolina. Coxe and his similar “monitizers” were also at work in the forests of eastern Kentucky.

One of Coxe’s partners was Robert Morris, a signer of the Declaration of Independence, who, unlike Coxe and his successors, pushed his “speculation” (another word for dispossession) beyond his means and ended up in debtor’s prison. Speculators such as Coxe, Morris, and Blount, in Tennessee, and earlier even George Washington in Kentucky, set the bar for land speculation. Coxe and partners began their empire by borrowing money (some $9,000) in order to purchase land at .09 cents an acre. The land held in Western North Carolina was, over the years, passed along to other investors who continued the process of dispossession and a long cycle of litigation that was not completed until the late 1920s and involved investors in England and in France. The dispossession is still going on. In Kentucky, the land and timber saga has much the same narrative and can be traced in the activity of surveyors, landowners, and speculators. We find suggestions of Coxe in the mining town of Coxton in Harlan County.

It is likely that Katherine Pettit sensed the importance of the lessons of history and how they could be written. Late in her life, she returned to trees. Like old friends, she embraced them and joined with well-known environmentalist Emma Lucy Braun to spend many of her last years fighting to save the remaining patriarchs of the forests in Kentucky and Ohio.

Again, this Pine Mountain student reminded us ,,,

All about me stately oak trees

Send their sprawling branches upward:

Sovereign they stand

O’er trees about them.

Yet drab they look, standing leafless,

While other trees

Of less dimension

Proudly display their Easter garments.……

George William Tye

POSTED BY: Helen H. Wykle

SEE ALSO:

LEON DESCHAMPS The Perfect Acre