“The death drive is not a principal. It even threatens every principality, every archontic primacy, every archival desire. It is what we will call, later on, le mal d’archive, ‘archive fever.'” Jacques Derrida, Archive Fever p.12

“To arrange a library is to practice in a quiet and modest way, the art of criticism.” Jorge Luis Borges (1973) Extraordinary Tales.

“… history has always been a critique of social narratives and, in this sense, a rectification of our common memory. Every documentary revolution lies along this same trajectory.” Paul Ricoeur (1973) Time and Narrative, p. 119

“Of all the places where documents pool and accrete, people’s desks are undoubtedly my favorite. They offer such a rich snapshot of modern life, of modern practices and pressures. Looking at one is a bit like examining a tidepool. At first it seems static and uninteresting. But once you start to pay attention, you begin to see what a complex eco-system is present, and how much richly structured and diverse activity is going on right before your eyes.” David M. Levy, (2001) Scrolling Forward: Making sense of documents in the digital age, p.121

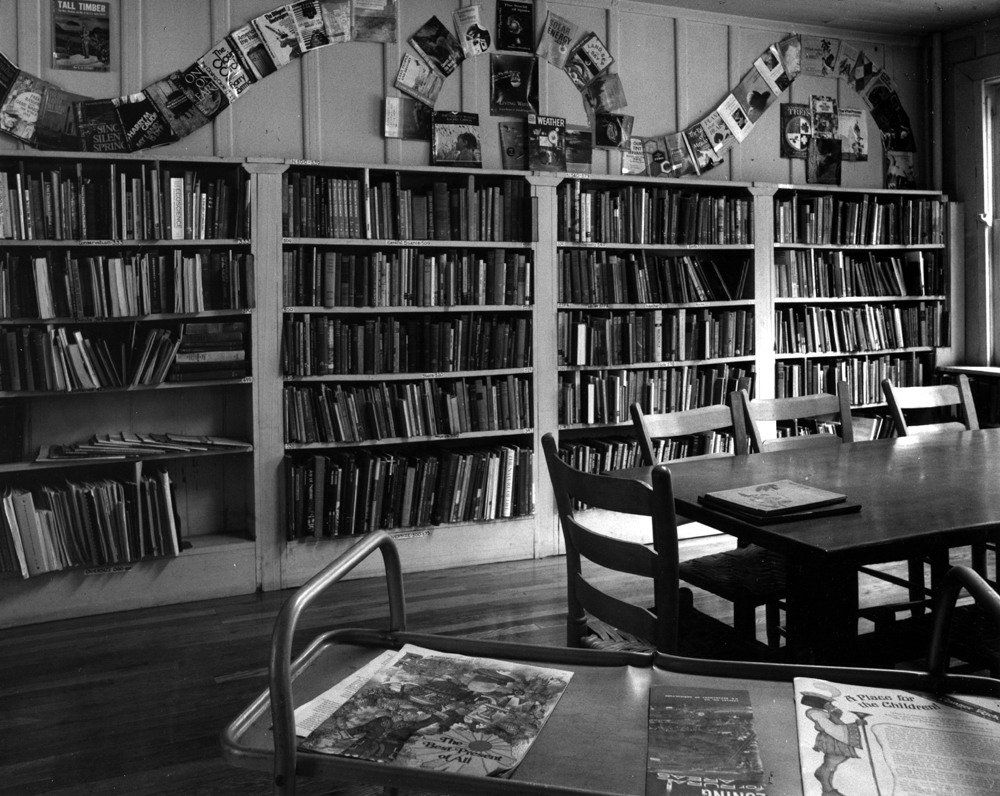

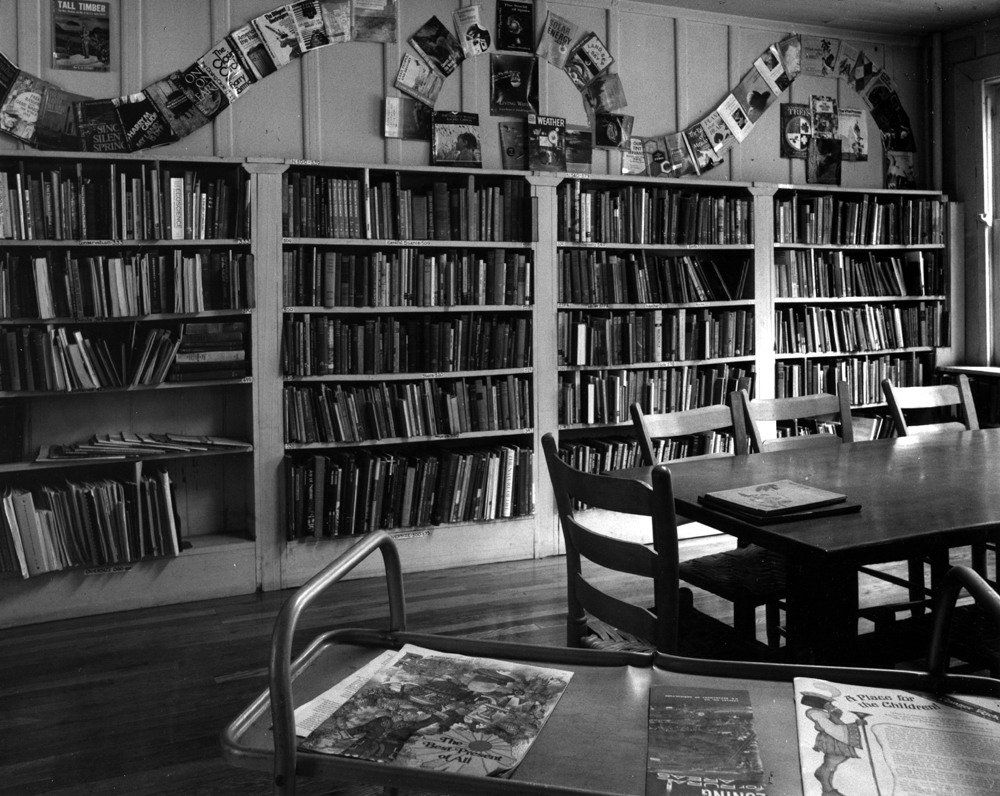

Boys House Library during reconstruction as Archive/Library room. 2017. [P1140220.jpg]

Melville Dewey, author of the Dewey Decimal Classification (DDC) System had a super sense of time and archiving. In fact, according to author Dee Garrison, “Dewey had an obsessive-compulsive desire to control his world — a characteristic often unjustly assigned to librarians and archivists, but justly assigned to oligarchs.”

“The attempt to control all eventualities, presented time as a special problem to Dewey. Time, an enemy to be overcome, was a threat to all his plans and projects. Since a guarantee of the future was his prime concern, he experienced time in the present as being wasted unless it were filled to the brim. The present did not have significance in itself because his interest was solely in the future . Dewey sought to dismiss time as a realistic limitation on his life. He craved certitude — desired to foretell, foresee, and exert control before the fact. Thus, Dewey’s lifelong concentration on detail is best understood as a measure of self -protection.”

Dee Garrison, (2003) Apostles of Culture [About Melville Dewey]

As seen in the above quotes, archives and archivists are not neutral, nor is there uniform agreement on what constitutes an “archive” and an “archivist.” [BUT — We do know that neither of the current keepers of this archive is an “oligarch.”] Further, there is no stability in today’s digital archive, and “archivist” seems to have lost its aura and proprietary ownership of all things, “archive.” As AI aims it’s voracious appetite toward archives, it will be remarkable to see what growth will interrupt archival interest and practice and to what purposes our archives will be used.

Archives, like closed collections of any kind, have often been maligned — seen as serving no function other than providing rent or bragging rights, or exclusivity in institutions across the world. However, archives small and large now challenge us to revisit the idea of both “archive” and “archive user.” Increasingly, institutions are realizing that archives have the potential for a broader reach and a societal impact. They need not be created only for the ubiquitous scholar-user, the scholar within academic institutions — or for the vested historian, or for the practiced genealogist. Their potential to serve a broader purpose continues to grow. But, for whose purpose? What purpose? Purposes? Scholar, curator, perpetrator, oligarch, …

TO KNOW AN ARCHIVE

To know an archive, and more importantly, to be the custodian of an “archive,” is an increasingly complex series of processes. To fully understand the institutional value and the evidentiary value of archival collections to their communities of creation is often not understood until one is immersed in the collections. Archives can create divides, but more frequently they bridge divides. Archives “talk” about and to their communities of interest. The archival material may often have a long tail of attached information that may not be readily seen, but soon enough it begs to be admired or disdained. These long tails (of information) are also often long tales; some already told and some waiting to be told…. and some purposely “bobbed.”

It is important that today’s archives and archivists bridge divides. It is important that they look to the communities that created long tails and tales of information gathering about them. But it is equally important that archivist also extend their vision and that of their patrons. Open archives, institutional archives, community archives, and personal collections now have a larger audience than they have ever known, as the current digital distribution processes make once hidden archives broadly available. And, within this growing production and accessibility of digital evidence is an even greater responsibility and complexity for the custodians, not the least of which is economic.

It is the belief of the creators and custodians of this digital archive, the Pine Mountain Settlement School Collections, that in the near future, archives and community collections will need to look outward to a broader spectrum of use and users. Exploring their definition and their distribution, the community archive can bring new knowledge and a sense of place and open the doors of discovery on little-known communities. The digital explosions of community archiving, of reaching marginalized communities, might be a noble desire, but without a doubt, these same collections can also be used for nefarious purposes or can distort the perceptions of both communities and their characterization of persons. Yet, closed archives do little for truth, for science, for education, or for building knowledge and trust. To do this work takes solid funding and commitment to archival excellence and longevity.

As a nation, a joined world, we are all of us the “Scholar,” the information gatherer, the interpreter, and the archivist, and we all need to guard our identity through responsible use and curation of our authentic shared information collections. At Pine Mountain Settlement School, we want to be good stewards and encourage the use of the PMSS archive on-site, where its full scope may be realized and where the purpose of the archive may be fully comprehended and respected. This is not always possible with no archivist on site. Digital access is only a partial solution to “closed” collections— and an imperfect one. But digital access and now AI assistance have opened the dialogue for accessible collections and universal users. At this moment in time, the call for collectively re-thinking archives and collections needs to be re-visited. Pine Mountain Settlement School Collections is attempting to do this using its own voice, in its own space, but it is still facing an up-hill slog in a world driven by entertainment.

On a basic human level, most of us want to know who our ancestors were as part of our own identity and possibly, — destiny. We want to explore gender bias, cultural diversity, morals, medical vulnerabilities, and the multiple mentalities that make us tick or make us sick. At Pine Mountain Settlement School and in the surrounding community, the current custodians want to continually evaluate our past practices against our current practices to determine if we are doing our best to sustain, organize, and retain the stories of the represented communities of interest. However, we are challenged to serve and reflect our community, while increasingly living outside it. To exercise responsible sensitivity, sensible environmentalism, and joy while living within the rich echoes of the past is no small challenge. Archives, museums, and places of historic interest need to be visited — not virtualized. Archives need fresh eyes that can look backward and look forward. Archives need a broader audience to expand our tolerance and exploration of new worlds and new understanding. We can move forward while looking backward. Knowing where we have been is as important as knowing where we are going.

Archives and collections gather the past, but they are also roadmaps pointing us to our future. As stewards — administrators, archivists, librarians, and collection managers —- and communities of interest —- we are charged with processing the PAST and the FUTURE. We can only do a good job if we are in a deep partnership with the entities that created and continue to create social memory — the archival communities of interest both near and far.

Berea College is one of the most important communities of interest to Pine Mountain Settlement School. In a land of contested borders AND contested information, we, the editors, have attempted to understand the challenges ahead and to move forward in this new digital world with some hope, caution, concern, and certainly, love of the Appalachian region that we share with our partner, Berea College.

We are reminded of and guided by Uncle William Creech’s “REASONS” and his hopes that we might provide something for those at “home” and those “overseas”—in other words, our vision is both inward and broadly outward, with what we hope is an intelligent and empathetic pursuit of the most representative historical knowledge, facts, and even tall tales that raise the dignity of people and place. The archive is the whole institution and every person at the School amd in the Community needs to be an archivist …

“It has never been the archivist’s responsibility to provide a descriptive finding aid that is responsive to all the questions of all of their users all of the time. … Closed archives affect historical understanding. … and empathy.”

Francis X. Blouin Jr. and William G. Rosenberg, (2011) Processing the Past: Contesting Authority in History and the Archives, p.155.

Imitation is not the answer. Disney does not model well for Appalachia. We have one of the most can-do and vibrant historical populations in the country. The Settlement School playbook has already been written into generations. Lessons, models, abound within our stories and our kindred. Kindness, generosity and common sense runs through our conversations. Our stories inspire. The institution is an archive. The community created it. Use it.

Why so many quotes? In many ways, an archive is a repository of quotes. We invite the user to find the quotes that resonate with their lives —- or better yet, we want the user to “be quotable” as they reflect on their discoveries in this and other archives and the many collections shared by the digital offerings of this increasingly complex twenty-first-century.

SEE ALSO:

Ann Angel Eberhardt (Co-editor)

Helen Hayes Wykle (Co-editor)

Pine Mountain Settlement School (Board of Trustees)

Berea College Archive

The editors – Ann Angel Eberhardt and Helen Hayes Wykle at PMSS. [Photo by Elanor Burkhard Brawner (1940 – Jan. 2022), Elanor, the first child born to staff members, Fred and Esther Burkhard, at the Pine Mountain Settlement School, and whose love for the institution only grew with each visit.]

ARCHIVE INDEX

ARCHIVE PMSS Mission Statement

ARCHIVE Our Vision for the PMSS Archive

ARCHIVE Pine Mountain Settlement School

ARCHIVE 1954-55 Library Report

ARCHIVE 1982 Fredrika Teute Overview

ARCHIVE 2002 Larry LaFollette Collections Report

ARCHIVE Management Documents and Commentary

ARCHIVE The Archive Turns a Corner

ARCHIVE PMSS Correspondence

DANCING IN THE CABBAGE PATCH POSTS (Helen Wykle) Personal responses to discoveries within and without the Archive.

A surprise hidden in the woodwork during boarding school days was discovered during the remodel of Boys House. Archive/Library Room. (We don’t endorse this, but found it archival, and a delightful example of archiving in a different mode!) [P1140236.jpg]

Boys House. Interior view of Community School Library, (c. the 1950s) [now the location of the current PMSS Archival Collections [II_08_boys_house_313c.jpg]

SETTLEMENT INSTITUTIONS OF APPALACHIA (SIA) Berea and Pine Mountain

The ARCHIVE of Pine Mountain Settlement School joins the historical collections of a small group of loosely identified rural settlement institutions of Appalachia. Under the title of Settlement Institutions of Appalachia (SIA) and funded by the National Endowment for the Arts in the early 1980s, the institutions established a partnership. The SIA project attempted to develop a conservation and preservation strategy that would protect its unique historical collections. Conceived as a call to attend to a little-recognized rural iteration of the larger Settlement Movement, the cooperative SIA endeavor focused on the common social aspects within the earlier urban social service work.

The SIA institutions of the Appalachia movement identified Appalachian rural “settlement” institutions and their archival collections as an “in situ” collective record of lived experience, with shared roots in earlier urban social services work. As “settlement ” institutions, the Eastern Kentucky institutions were individually unique, and they still remain so. They were associated with the ideas of the earlier urban social service programs in Chicago and in Boston and other urban centers, but should not be confused with the models of these larger urban settlement movements.

The archival collections held by the early rural settlement institutions were believed to be at risk of being lost to the more well-known national settlement movement. Collectively, the Settlement Institutions of Appalachia certainly revealed that the studied institutions in Appalachia were more homogeneous than those found in the various cities that established “Settlement Houses.” The rural settlements held in common many similar records of an often described, but poorly characterized, settlement ethos. Some have pointed to the rural settlement movement as strongly indebted to local religious homogeneity. Others have brought forward the physical siting of the rural schools.

While city and country revealed marked differences in their approach to ideas gleaned from the settlement movement, the cultural overlay was often shaped by media that preferred to define and characterize Appalachian Settlement communities as comprised of stereotyped people outside the social practices of the time. On closer look, the geography, history, and sociology of Appalachia did not always conform to the national and international social experiment called the “Settlement Movement” that sought to address race relations, poverty, and cultural assimilation. For that reason and more, the Appalachian social settlements have often been difficult to define as a genre.

The Settlement Institutions of Appalachia (SIA) were certainly unique in their rural identity. They did not share common missions or the objective of addressing immigrant populations found in large urban settings. Yet, the urban models, their philanthropy as reflected in their histories, and their programming were adapted easily into the rural areas of Appalachia. These new “Settlement” institutions borrowed heavily from the Chicago work of Jane Addams at Hull House and other earlier urban settlement houses. Both urban and rural settlements had a stake in providing social, educational, and, many times, religious resources to disadvantaged populations. Poverty was perhaps their most common service denominator. The ravages of poverty and poor educational opportunity were still evident in the urban centers at the end of the nineteenth century, but the rural settlement centers were just being formed at the beginning of the twentieth century. By the 1980s, the history of these early social service centers was at risk of loss. Further, in many of the Appalachian communities in the early 1980s, the SIA initiative sought to bring the social needs of the people of Appalachia to the attention of the country and the world. The story of poverty was a keen fit with the growing need to address Appalachian poverty and educational deficits.

Using elements derived from the broader national and international history of the Settlement Movements, the Pine Mountain Settlement archival initiative has sought to secure a place for the rural settlement’s origins in the larger and earlier social movement. While the methods and objectives of these institutions often varied dramatically, some believed that their archives would capture this diversity as well as the similarities and differences in the communities they served. The diverse archival records, social, religious, and political, captured local translation of the larger social movement in each SIA institution and how the Settlement Movement persisted — or didn’t persist through history. The 1983 SIA archival project and its difficult medium, –the archive —could essentially “freeze” the institutional history for future scholars. The photographs, the transcribed conversations, film clips, craft, art, and the evolution of the built environment were unique in their historic evolution in rural America. Saving their history to microfilm was in the interest of the future of each of the SIA sites.

The Settlement Institutions of Appalachia archive project anticipated that their “save” would protect original documents and images in what was then the new medium, for all time. Microfilm does this —- perhaps not as long as “for all time”, but it was the best option at the time. It was a conservation medium popular in the 1980s for its supposed longevity if stored under proper conditions. No one imagined the floods as devastating as those seen in today’s weather scene. The medium of microfilm continues to be appreciated for its staying power, but its use has dropped dramatically as using microform proved tedious for all but the devoted scholar. Over the years, the hum of the microfilm machine slowly went silent as digital media, born in the 1980s, began to replace it.

The aggregated microfilm collection, a physical format, was lost to the digital tsunami. The microfilm stations soon served only the most dedicated researchers at central locations such as Berea and the University of Kentucky. Further, students had no appetite or patience for microfilm. Microfilm lacked the immediate reward of instantaneous retrieval found in the more exciting original record or the more fluid digital record. And, many of the institutions were not willing to send original materials to Berea. Pine Mountain was one of those institutions.

But, of note, in the 1980s, microform had a good ability to live up to its “preservation” lifespan. As time progressed, it was lauded for its stability. It allowed the duplication of collections and the ability to provide a longer term of life for many poorly stored institutional collections. But, obviously, it is less than an engaging resource to access and has limited full use of the information. What it eventually did was to ensure that collections would become increasingly inaccessible and would continue to limit the ability to do comparative research with ease. As years passed, only researchers with both time and resources would travel and sit for hours with a microform reader.

Nevertheless, not having the advantage of the prescience of the digital revolution beginning in the late 1990s, microfilm was chosen for the 1980s SIA archival preservation project. It should be pointed out that the Society of American Archivists pushed these long-lived gifts into many collections with their microfilm campaign. The documents and “contact prints” that duplicated the original material allowed for “off-site” storage and brought many institutional holdings together in one location, such as the Berea College, Kentucky, repository for the SIA materials. The contact prints (copies) of the photographs in the institutional collections were used to create duplicate sets of the fragile photograph originals and were stored with the microfilmed documents at Berea, as well as copies given to the institutions that shared the photographs. This preservation effort was not in vain.

The SIA proposal was founded on sound principles of current archival practice and good preservation intentions, and most partners came to join the project. There were some partners, however, that were pushed into the collective effort, kicking and grumbling. Pine Mountain Settlement was one partner that did not meet the project with enthusiasm and pushed strongly against their inclusion in the project, initially declining to partner in the SIA project. [See NOTES]

The SIA correspondence regarding the Pine Mountain Settlement School institution’s eventual formal agreement or “buy-in” is a record of institutional anxiety on many sides. The University of Kentucky (UK) assisted in the collections transfer process. Kentucky had the equipment to manage the technical microform and film transfers. The copied material, microfilm, and contact prints of the photographs generated considerable debate. The photographs presented a point of concern as copyright concerns grew along with the new media. It was a concern at the core of the various visual collections and remains a concern today. Early on there was no formal accounting of how the images from the various institutions were to be used, even though standard attribution to the original institutions was closely followed.

Another loss for the original institutions and the researchers was the “go-to-place” experience. However, there were significant benefits to researchers who wished to study or compare and contrast multiple rural settlement schools. Berea wisely collected and joined additional original archival materials donated by various donors and resources. For many years, this collected body of SIA materials represented a central and “go-to” place for researchers interested in the Central and Southern Appalachians Settlement movement. The added collections and SIA archives were and are of value to researchers. The dilemma was access to the material for those communities responsible for the creation of the collections. The small institutions that had created the records of their history did not have direct management of their “story” under the new technology demands. The digital revolution has provided far more access, but less stability and now, today, AI has a new set of questions..

In the deep discussion that preceded the agreement of Pine Mountain Settlement School to participate in the SIA project, it became a highly sensitive topic in the Settlement School and researcher communities. Researchers, often overly dependent on the microfilm and the accompanying archival materials, clearly missed the essence of “place,” and few researchers had the patience to methodically move through reels of film to try to grasp the essence of a community. Compounding the research picture was the reluctance of some researchers to visit the Settlement institutions and which can be found in some of the shallow research derived from the troublesome materials and methods. Further, the Settlement institutions soon rarely ventured to Berea to go through their own microform holdings, creating a distance from the institutions’ history and the lessons of history. Also, new material related to the SIA institutions was most often directed to Berea, further fracturing the fabric of the local collections and archives from their origins.

However, it is important to note that the SIA institutions, such as Hindman and Pine Mountain Settlement, continued to accumulate records on site and, like Pine Mountain, their institutional archives did not end in 1983, but they continued to build on the returned original records and did not pursue further microfilming. Thus, since 1983, many of the Settlement School archives and Records collections have grown. Today, the condition and the scale of the institutional records of the original SIA sites vary, and their institutional records are stored (or not) under varying conditions.

PMSS Collections: Issues

The ARCHIVE at Pine Mountain Settlement School IS NOT just the surrogate special collection captured within the earlier microform celluloid and the contact prints. That collection is only a small fraction of the Pine Mountain Settlement School ARCHIVE.

Efforts to address collections gathered from 1983 forward are an important need still facing the School and many other partners. The need to re-house and organize those later records continues and is a critical need. It is the post-1983 collections that pose the greatest risks to collections. As the School hosts more reunions and more octogenarians want to recall their Boarding School years, and the younger generations in the Community want to fill in gaps in their family histories, the need to provide manageable, secure, and sensible access to the institutional records continues to grow.

Today’s records and property management do not fully acknowledge the collection context and its inherent issues. But then, the Pine Mountain Settlement School is an uneasy captive that does not easily yield up its secrets, joys, and sense of place. The Pine Mountain Settlement School archival materials at Berea were pulled from their original sites with good intentions, but the process was made uncomfortable from the beginning. The local correspondence suggests that the complexity of the SIA relationships grew.

Living history does not capture well in static systems. When history is asked to live within its surrogates of celluloid, zeros and ones, in multi-generation copy photographs, in tightly regulated boxes, and in closed shelves, it often struggles with identity. Yet, collections can also die from neglect, from being placed in a closed-door mausoleum or left to the elements and disorder. Institutional archives can suffer from a kind of cancer of abandonment from within when their institutions fail to recognize the need for responsible collection supervision of fragile materials on site. Archivists are few and far between. It is a special mania, or as some have said, a “fever” … but a good fever and one desperately needed in small collections and archives across the country.

The dilemmas inherent in the Pine Mountain Settlement School surrogates at Berea College and the complex and poorly processed and integrated ARCHIVE at the Settlement School present issues in any intelligent articulation of the Pine Mountain Settlement School community as it has grown.

With the rise of Artificial Intelligence, another iteration of collection management is on the horizon. How will new technologies capture and share the forests and the creatures, the arts and the crafts, the life and livelihood of the community, governance and administration, and the past and emergent arrangement of history? …. It remains to be known.

PMSS and Berea College

See Also: ARCHIVE 1983 PMSS Records on Berea College Microfilm

The following is Berea’s description of the Pine Mountain Settlement School collections held on microfilm at the College:

Restrictions: Records and photographs can be accessed through the Reading Room, Berea College Special Collections and Archives, Hutchins Library, and Berea College.

Rights: Regarding records contained in the collection:

Pine Mountain Settlement School records were collected and organized in 1982. Those having administrative, legal, or historical value were microfilmed at the Kentucky Department for Libraries and Archives and all were then returned to Pine Mountain. The resultant microfilm master negative is owned by Berea College. A user copy is available for researchers. Berea College does not own the copyright for the manuscripts or printed documents included in this microfilm edition. Therefore, it is the researcher’s responsibility to secure permission to publish from Pine Mountain Settlement School or its successors and assigns. Due to the personal information they contain, some records such as student and personnel records may be RESTRICTED.

Regarding photographs in the collection:

Pine Mountain Settlement School photographs were organized and copied in 1985. The copy negatives and a set of copy prints are owned by Berea College. A second set of copy prints and all originals were returned to Pine Mountain Settlement School. Permission has been granted by Pine Mountain Settlement School for Berea College to reproduce all or part of the school’s photographs and to use them in slide or film presentations, display them, or loan them for display, and to allow their use by researchers for reproduction and publication. The proper credit line for all of the above uses shall be, “Pine Mountain Settlement School Photographic Collection, Berea College Southern Appalachian Archives.” Records and photographs can be accessed through the Reading Room, Berea College Special Collections and Archives, Hutchins Library, Berea College. https://berea.libraryhost.com/index.php?p=collections/controlcard&id=42

THE PMSS ARCHIVE in Context

The standard film preservation practice of contact prints for photograph material and microfilm for documents has given the Pine Mountain Settlement School collections some security but it fails to place the history within its context — or context within its broader settlement institutional histories — depending on the vantage point. While the valuable preservation processes only scratched the surface in 1983-1984, they stirred up a rich soil that is the ARCHIVE of Pine Mountain now evolving and growing within a digital world. That digital world is a world that is redefining the archive and with it, “information” as well as preservation, conservation, ownership, and ultimately physical storage and on-site accessibility.

Claude Shannon, who along with Alan Turing, was a noted cryptographer and code breaker, told us long ago that “Information, though related to the everyday meaning of the word, should not be confused with it.” This can certainly be contemplated by collections gathered within their communities of origin. Information is, as our contemporary author James Gleick tells us in his book The Information: A History, a Theory, a Flood (2011)*, that information as an entity is “uncertainty, surprise, difficulty, and entropy.” These views describe many of the small local archives scattered throughout the world — and are suggestive of the enigmatic nature of the Pine Mountain Settlement School archive. It also describes the other Settlement institutions that joined Pine Mountain in the Berea College Settlement Institutions of Appalachia archive.

*[See: James Glick, The Information: A History, a Theory, a Flood, 2011]

At Pine Mountain Settlement School the deep forest, open fields, pristine air and water, the surrounding community with its sincere, bright, devotional, and struggling populations; the 24 buildings, stonework, trails, play equipment, cultural collections (most notably Native American artifacts and Pioneer tools), weaving, native botanical habitats, birds, treasured trees, etc.; the staff that annually hold programs regarding their care; and the many special events that stick to the visual and auditory memory of those who have stayed long enough to be captured by the magic of the place ——–this is what is hidden beneath the standard secondary descriptions of place. In reality, Pine Mountain is a place of notes hidden in walls, in boxes, in memories. The personal letters of students describing their educational experience, and the passionate letters of the defenders of Pine Mountain Settlement School experiences with “Lands Unsuitable for Mining,”, walks to Trillium Rock dressed in its annual spring-time garment, squeezing fat bodies through “Split Rock”, a child’s first glimpse of a beaver, or a dragonfly resting on the mossy rock of Isaac’s Creek, etc., etc. …..

In the deep and isolated valley sandwiched between two mountains, it is the undiscovered and implied information in the tangible that forms the deep definitions of place. “Place” is often filled with “uncertainty, surprise, difficulty, and entropy” A sense of place is what this ARCHIVAL RECORD attempts to capture and reveal and encourage. It is not just the structured list of objects, dates, names, deeds, photographs, and now media that one often finds in institutional and many online archives — (though there are many of those inscrutable works in the Pine Mountain Settlement School archive.) What sticks to the senses are the first-hand accounts and the stories that still abound in the School record. It is also the untold stories that happen when the environment surrounds and informs the written and photographed record.

The archival collection at Pine Mountain Settlement is an infosphere of collections. It is found in a multitude of dark or brilliant corners of personal lives that overlapped with the physical site of Pine Mountain Settlement School. It is where those with connections to the area may discover their own true nature and where an understanding of the Pine Mountain Settlement School community is uniquely and often privately revealed and where it resonates — for good or ill. No matter the place of birth, Pine Mountain Settlement is born of the community, but it is the community of us all. Telling the story of an institution, of a community as complex as Pine Mountain is not a tidy business … but, then, neither are our lives.

PINE MOUNTAIN SETTLEMENT SCHOOL Collections

The collections gathered by Pine Mountain Settlement School follow a selective process that sometimes aggregates in a seemingly arbitrary manner. This is in part due to the nature of collections when assembled and brought forward through the interesting discoveries of various keepers [archivists]. The keepers’ interests and their stories sometimes mingle and pull selected facts forward — as it should be. The Pine Mountain collections of letters, photos, poetry, and perfidery discovered in the collections display the stamps of eras, personalities, interests, politics, religious focus, etc. The collections also display attempts of the contributors to capture their common moments, their focus, their reflections, their memories, as they associated with the information and the institution. Sometimes the whole is a crazy quilt of the anguish and joy and pessimism and optimism of students of the Boarding School years and the Community School, past Directors at odds with staff, and volunteers, friends of the School, and interested visitors discovering unknowns and sometimes misrepresenting them. The many who have streamed through this remote corner of Kentucky have contributed to the many diverse and associated documents and to the institutional history of this unique place.

Much more remains to be discovered regarding the creation of the collections — the creation of the history of place. The journey of discovery has only begun to explore what is hidden in the memories, reflections, and even the fabrications of those who live and lived there. Archival collections are a fluid stream of history and story. We, the keepers of history, do not doubt that later discoveries will capture more enigmatic and individual adventures — more hidden history in this magical place that we have “cherry-picked”. In the first one-hundred-plus years, the gathering, re-gathering, and discovering that went into the collective archive all point the way to a myriad of stories, multiple definitions, and much greater understanding of a unique corner of Appalachia. But, the stories that each user finds in the ARCHIVAL collections are their discoveries and theirs to re-tell.

The Pine Mountain Settlement School Collections represent the near but also the far communities that share the need to know, explain, love, hate, and wrestle memories and ideas into an understanding of self and place. An archive is a collection about and for both near and far communities. It is an idea, a place, a person, a vision, love, hate, anger, fear, frustration, and a warm, crazy quilt held tightly together by generational and emotional glue. If the near community, and the far communities of interest, can be moved by the spirit of place, surely Pine Mountain will continue to inspire and inform and grow, and so will the archive. The surface has barely been scratched.

Is the whole a reflection of the reality of the institution? Is the archive the reality of Pine Mountain Settlement School? How does one even begin to answer that question? Locking history into a model or into a singular destiny seems in many ways to imprison the joy of individual discovery—of building one’s own history … the chapter in one’s own life journey that is never … whole.

As seen in the records noted below, archives/collections are often contested spaces. They can both evoke and provoke as they inevitably require emotional engagement. In this age of contestation, archives should require this level of emotional engagement. To love, hate, reflect, correct, change, question, and hold close a discovered idea — all these emotions and civic and social responses — need to be guided by intellect and informed search methods when entering an archive. Who is there to guide? What comes from the experience may be scholarly, personal, contested, admired, despised, or revered, but it needs, above all, to be honest, placed within its context, used — and, above all, it needs to be preserved as a beating heart, as soul-food for the future.

TO DISCOVER, TO USE, AND TO LEARN Through the Archives

“Most of the biosphere cannot see the infosphere, it is invisible, a parallel universe humming with ghostly inhabitants … We are aware of the many species of information …” …. a meme for example

Fred Dretske (1981) Knowledge and the Flow of Information (as quoted by James Gleick)

Of growing importance —-“In the beginning there was information. The word came later… The transition was achieved by the development of organisms with the capacity for selectively exploiting this information in order to survive and perpetuate their kind. We keep them alive in air-conditioned server farms. But we cannot own them … who is master and who is slave?”

James Gleick, (2011) The Information: A History, a Theory, a Flood, p. 323

“The death drive is not a principal. It even threatens every principality, every archontic primacy, every archival desire. It is what we will call, later on, le mal d’archive, ‘archive fever.'” Jacques Derrida, Archive Fever p.12

“To arrange a library is to practice in a quiet and modest way, the art of criticism.” Jorge Luis Borges (1973) Extraordinary Tales.

“… history has always been a critique of social narratives and, in this sense, a rectification of our common memory. Every documentary revolution lies along this same trajectory.” Paul Ricoeur (1973) Time and Narrative, p. 119

“Of all the places where documents pool and accrete, people’s desks are undoubtedly my favorite. They offer such a rich snapshot of modern life, of modern practices and pressures. Looking at one is a bit like examining a tidepool. At first it seems static and uninteresting. But once you start to pay attention, you begin to see what a complex eco-system is present, and how much richly structured and diverse activity is going on right before your eyes.” David M. Levy, (2001) Scrolling Forward: Making sense of documents in the digital age, p.121

Boys House Library during reconstruction as Archive/Library room. 2017. [P1140220.jpg]

Melville Dewey, author of the Dewey Decimal Classification (DDC) System had a super sense of time and archiving. In fact, according to author Dee Garrison, “Dewey had an obsessive-compulsive desire to control his world — a characteristic often unjustly assigned to librarians and archivists, but justly assigned to oligarchs.”

“The attempt to control all eventualities, presented time as a special problem to Dewey. Time, an enemy to be overcome, was a threat to all his plans and projects. Since a guarantee of the future was his prime concern, he experienced time in the present as being wasted unless it were filled to the brim. The present did not have significance in itself because his interest was solely in the future . Dewey sought to dismiss time as a realistic limitation on his life. He craved certitude — desired to foretell, foresee, and exert control before the fact. Thus, Dewey’s lifelong concentration on detail is best understood as a measure of self -protection.”

Dee Garrison, (2003) Apostles of Culture [About Melville Dewey]

As seen in the above quotes, archives and archivists are not neutral, nor is there uniform agreement on what constitutes an “archive” and an “archivist.” [BUT — We do know that neither of the current keepers of this archive is an “oligarch.”] Further, there is no stability in today’s digital archive, and “archivist” seems to have lost its aura and proprietary ownership of all things, “archive.” As AI aims it’s voracious appetite toward archives, it will be remarkable to see what growth will interrupt archival interest and practice and to what purposes our archives will be used.

Archives, like closed collections of any kind, have often been maligned — seen as serving no function other than providing rent or bragging rights, or exclusivity in institutions across the world. However, archives small and large now challenge us to revisit the idea of both “archive” and “archive user.” Increasingly, institutions are realizing that archives have the potential for a broader reach and a societal impact. They need not be created only for the ubiquitous scholar-user, the scholar within academic institutions — or for the vested historian, or for the practiced genealogist. Their potential to serve a broader purpose continues to grow. But, for whose purpose? What purpose? Purposes? Scholar, curator, perpetrator, oligarch, …

TO KNOW AN ARCHIVE

To know an archive, and more importantly, to be the custodian of an “archive,” is an increasingly complex series of processes. To fully understand the institutional value and the evidentiary value of archival collections to their communities of creation is often not understood until one is immersed in the collections. Archives can create divides, but more frequently they bridge divides. Archives “talk” about and to their communities of interest. The archival material may often have a long tail of attached information that may not be readily seen, but soon enough it begs to be admired or disdained. These long tails (of information) are also often long tales; some already told and some waiting to be told…. and some purposely “bobbed.”

It is important that today’s archives and archivists bridge divides. It is important that they look to the communities that created long tails and tales of information gathering about them. But it is equally important that archivist also extend their vision and that of their patrons. Open archives, institutional archives, community archives, and personal collections now have a larger audience than they have ever known, as the current digital distribution processes make once hidden archives broadly available. And, within this growing production and accessibility of digital evidence is an even greater responsibility and complexity for the custodians, not the least of which is economic.

It is the belief of the creators and custodians of this digital archive, the Pine Mountain Settlement School Collections, that in the near future, archives and community collections will need to look outward to a broader spectrum of use and users. Exploring their definition and their distribution, the community archive can bring new knowledge and a sense of place and open the doors of discovery on little-known communities. The digital explosions of community archiving, of reaching marginalized communities, might be a noble desire, but without a doubt, these same collections can also be used for nefarious purposes or can distort the perceptions of both communities and their characterization of persons. Yet, closed archives do little for truth, for science, for education, or for building knowledge and trust. To do this work takes solid funding and commitment to archival excellence and longevity.

As a nation, a joined world, we are all of us the “Scholar,” the information gatherer, the interpreter, and the archivist, and we all need to guard our identity through responsible use and curation of our authentic shared information collections. At Pine Mountain Settlement School, we want to be good stewards and encourage the use of the PMSS archive on-site, where its full scope may be realized and where the purpose of the archive may be fully comprehended and respected. This is not always possible with no archivist on site. Digital access is only a partial solution to “closed” collections— and an imperfect one. But digital access and now AI assistance have opened the dialogue for accessible collections and universal users. At this moment in time, the call for collectively re-thinking archives and collections needs to be re-visited. Pine Mountain Settlement School Collections is attempting to do this using its own voice, in its own space, but it is still facing an up-hill slog in a world driven by entertainment.

On a basic human level, most of us want to know who our ancestors were as part of our own identity and possibly, — destiny. We want to explore gender bias, cultural diversity, morals, medical vulnerabilities, and the multiple mentalities that make us tick or make us sick. At Pine Mountain Settlement School and in the surrounding community, the current custodians want to continually evaluate our past practices against our current practices to determine if we are doing our best to sustain, organize, and retain the stories of the represented communities of interest. However, we are challenged to serve and reflect our community, while increasingly living outside it. To exercise responsible sensitivity, sensible environmentalism, and joy while living within the rich echoes of the past is no small challenge. Archives, museums, and places of historic interest need to be visited — not virtualized. Archives need fresh eyes that can look backward and look forward. Archives need a broader audience to expand our tolerance and exploration of new worlds and new understanding. We can move forward while looking backward. Knowing where we have been is as important as knowing where we are going.

Archives and collections gather the past, but they are also roadmaps pointing us to our future. As stewards — administrators, archivists, librarians, and collection managers —- and communities of interest —- we are charged with processing the PAST and the FUTURE. We can only do a good job if we are in a deep partnership with the entities that created and continue to create social memory — the archival communities of interest both near and far.

Berea College is one of the most important communities of interest to Pine Mountain Settlement School. In a land of contested borders AND contested information, we, the editors, have attempted to understand the challenges ahead and to move forward in this new digital world with some hope, caution, concern, and certainly, love of the Appalachian region that we share with our partner, Berea College.

We are reminded of and guided by Uncle William Creech’s “REASONS” and his hopes that we might provide something for those at “home” and those “overseas”—in other words, our vision is both inward and broadly outward, with what we hope is an intelligent and empathetic pursuit of the most representative historical knowledge, facts, and even tall tales that raise the dignity of people and place. The archive is the whole institution and every person at the School amd in the Community needs to be an archivist …

“It has never been the archivist’s responsibility to provide a descriptive finding aid that is responsive to all the questions of all of their users all of the time. … Closed archives affect historical understanding. … and empathy.”

Francis X. Blouin Jr. and William G. Rosenberg, (2011) Processing the Past: Contesting Authority in History and the Archives, p.155.

Imitation is not the answer. Disney does not model well for Appalachia. We have one of the most can-do and vibrant historical populations in the country. The Settlement School playbook has already been written into generations. Lessons, models, abound within our stories and our kindred. Kindness, generosity and common sense runs through our conversations. Our stories inspire. The institution is an archive. The community created it. Use it.

Why so many quotes? In many ways, an archive is a repository of quotes. We invite the user to find the quotes that resonate with their lives —- or better yet, we want the user to “be quotable” as they reflect on their discoveries in this and other archives and the many collections shared by the digital offerings of this increasingly complex twenty-first-century.

SEE ALSO:

Ann Angel Eberhardt (Co-editor)

Helen Hayes Wykle (Co-editor)

Pine Mountain Settlement School (Board of Trustees)

Berea College Archive

The editors – Ann Angel Eberhardt and Helen Hayes Wykle at PMSS. [Photo by Elanor Burkhard Brawner (1940 – Jan. 2022), Elanor, the first child born to staff members, Fred and Esther Burkhard, at the Pine Mountain Settlement School, and whose love for the institution only grew with each visit.]

ARCHIVE INDEX

ARCHIVE PMSS Mission Statement

ARCHIVE Our Vision for the PMSS Archive

ARCHIVE Pine Mountain Settlement School

ARCHIVE 1954-55 Library Report

ARCHIVE 1982 Fredrika Teute Overview

ARCHIVE 2002 Larry LaFollette Collections Report

ARCHIVE Management Documents and Commentary

ARCHIVE The Archive Turns a Corner

ARCHIVE PMSS Correspondence

DANCING IN THE CABBAGE PATCH POSTS (Helen Wykle) Personal responses to discoveries within and without the Archive.

A surprise hidden in the woodwork during boarding school days was discovered during the remodel of Boys House. Archive/Library Room. (We don’t endorse this, but found it archival, and a delightful example of archiving in a different mode!) [P1140236.jpg]

Pine Mountain Settlement School

Series 00: ARCHIVES

About the Pine Mountain Settlement School Collections

A surprise archival record thumb-tacked to the woodwork of the Archive wall. Discovered the remodel of the room to accommodate shelving for the archival records. Archive/Library room in Boys House. [P1140235.jpg]

TAGS: About the Pine Mountain Settlement School collections, local history, Pine Mountain Valley, National Heritage site, indexing, finding aids, cataloging, assessment reports, preservation, archive resources, inventory guidelines, disposition schedules, archive and special collections rationale, Helen Wykle, Ann Angel Eberhardt, Preston Jones, Pine Mountain Settlement School Board of Trustees, Education Committee, Elanor Burkhard Brawner, Mary Rogers, volunteers

ARCHIVE – ABOUT THE PINE MOUNTAIN

SETTLEMENT SCHOOL COLLECTIONS

OUR VISION

ARCHIVES/COLLECTIONS

The ARCHIVE at Pine Mountain Settlement is more than just a room of material about dead people and disappeared buildings and mountainsides. It is the aggregate of a fully sentient institution and people. The hidden note tacked inside the wall of the former Boy’s House dormitory and now housing the Pine Mountain Settlement School Collections points to the important fact that the entire institution is an archive, a special collection, a library, a museum, a national treasure, and a very difficult entity to fully gather under the rubric of what many believe to be a traditional “ARCHIVE.” It is a protected National Register of Historic Places site, but that is a preservation title that only begins the process of discovery described by the material culture of this historic place only partially detailed in this online archive.

The archival collections at Pine Mountain Settlement School are integral to an understanding of the institution in Harlan County, Kentucky. The archival collections are the documented references to the institution’s history, the surrounding community, and the people who joined in creating that history. Pine Mountain Settlement is also an experiment in education. Visions, subtle and sometimes not-so-subtle, may be read in the archival records stored in the Library at the School and continuously created for more than 100 years.

As one of the important landmarks on the National Historic Register, Pine Mountain Settlement School joins many important sites that celebrate the nation’s history. Pine Mountain has much to say, to teach, and to celebrate regarding the Settlement Movement as it was redefined in the Central and Southern Appalachians. Again, to emphasize, the discreet collections of material at and in Pine Mountain Settlement School’s holdings include the traditional materials as well as the physical institution itself.

In truth, there is little to distinguish between “archive” and “collection” at Pine Mountain Settlement. As the current keepers continually point out, the Pine Mountain Settlement School is in its entirety the buildings, grounds, photographs and documents, realia, artifacts, and recorded material about the School, etc. But the archive is more. It is also the communities surrounding the School. The “archive” is a collection of the whole of the institution and the community it serves. This larger archive/collections/place is a collective memory. It is well described in the many distinct and discreet materials that live within and without the walls of the Pine Mountain Library building. All of this collective memory is here referred to as “The Archive,” as that is the focus of this finding aid.

The archive rooms at the Library (formerly called “Boys’ House”) contain materials found frequently in familiar institutional “archives”. Within boxes and in the various storage rooms, are collections of books, maps, paintings, drawings, photographs, various media (audio, and video recordings, CDs, etc.), woven materials, pottery, carvings, books, ephemera, looms, chairs, tables, paintings, rocks, Native American flint collections, guns, iron pots and kettles, and more. The object collections often hold subtle and deep history, yet, to grasp the full collective archive is to be THERE — on site, walking among and within the built environment, talking to the people, surrounded by the flora and fauna, and breathing in the history of the place, the idea, the Settlement School. There is more to know when an archive thrives within its rich entirety, wrapped within the full institutional history and community that created its collections, its memory, and its idea.

Boys House. Interior view of Community School Library, (c. the 1950s) [now the location of the current PMSS Archival Collections [II_08_boys_house_313c.jpg]

SETTLEMENT INSTITUTIONS OF APPALACHIA (SIA) Berea and Pine Mountain

The ARCHIVE of Pine Mountain Settlement School joins the historical collections of a small group of loosely identified rural settlement institutions of Appalachia. Under the title of Settlement Institutions of Appalachia (SIA) and funded by the National Endowment for the Arts in the early 1980s, the institutions established a partnership. The SIA project attempted to develop a conservation and preservation strategy that would protect its unique historical collections. Conceived as a call to attend to a little-recognized rural iteration of the larger Settlement Movement, the cooperative SIA endeavor focused on the common social aspects within the earlier urban social service work.

The SIA institutions of the Appalachia movement identified Appalachian rural “settlement” institutions and their archival collections as an “in situ” collective record of lived experience, with shared roots in earlier urban social services work. As “settlement ” institutions, the Eastern Kentucky institutions were individually unique, and they still remain so. They were associated with the ideas of the earlier urban social service programs in Chicago and in Boston and other urban centers, but should not be confused with the models of these larger urban settlement movements.

The archival collections held by the early rural settlement institutions were believed to be at risk of being lost to the more well-known national settlement movement. Collectively, the Settlement Institutions of Appalachia certainly revealed that the studied institutions in Appalachia were more homogeneous than those found in the various cities that established “Settlement Houses.” The rural settlements held in common many similar records of an often described, but poorly characterized, settlement ethos. Some have pointed to the rural settlement movement as strongly indebted to local religious homogeneity. Others have brought forward the physical siting of the rural schools.

While city and country revealed marked differences in their approach to ideas gleaned from the settlement movement, the cultural overlay was often shaped by media that preferred to define and characterize Appalachian Settlement communities as comprised of stereotyped people outside the social practices of the time. On closer look, the geography, history, and sociology of Appalachia did not always conform to the national and international social experiment called the “Settlement Movement” that sought to address race relations, poverty, and cultural assimilation. For that reason and more, the Appalachian social settlements have often been difficult to define as a genre.

The Settlement Institutions of Appalachia (SIA) were certainly unique in their rural identity. They did not share common missions or the objective of addressing immigrant populations found in large urban settings. Yet, the urban models, their philanthropy as reflected in their histories, and their programming were adapted easily into the rural areas of Appalachia. These new “Settlement” institutions borrowed heavily from the Chicago work of Jane Addams at Hull House and other earlier urban settlement houses. Both urban and rural settlements had a stake in providing social, educational, and, many times, religious resources to disadvantaged populations. Poverty was perhaps their most common service denominator. The ravages of poverty and poor educational opportunity were still evident in the urban centers at the end of the nineteenth century, but the rural settlement centers were just being formed at the beginning of the twentieth century. By the 1980s, the history of these early social service centers was at risk of loss. Further, in many of the Appalachian communities in the early 1980s, the SIA initiative sought to bring the social needs of the people of Appalachia to the attention of the country and the world. The story of poverty was a keen fit with the growing need to address Appalachian poverty and educational deficits.

Using elements derived from the broader national and international history of the Settlement Movements, the Pine Mountain Settlement archival initiative has sought to secure a place for the rural settlement’s origins in the larger and earlier social movement. While the methods and objectives of these institutions often varied dramatically, some believed that their archives would capture this diversity as well as the similarities and differences in the communities they served. The diverse archival records, social, religious, and political, captured local translation of the larger social movement in each SIA institution and how the Settlement Movement persisted — or didn’t persist through history. The 1983 SIA archival project and its difficult medium, –the archive —could essentially “freeze” the institutional history for future scholars. The photographs, the transcribed conversations, film clips, craft, art, and the evolution of the built environment were unique in their historic evolution in rural America. Saving their history to microfilm was in the interest of the future of each of the SIA sites.

The Settlement Institutions of Appalachia archive project anticipated that their “save” would protect original documents and images in what was then the new medium, for all time. Microfilm does this —- perhaps not as long as “for all time”, but it was the best option at the time. It was a conservation medium popular in the 1980s for its supposed longevity if stored under proper conditions. No one imagined the floods as devastating as those seen in today’s weather scene. The medium of microfilm continues to be appreciated for its staying power, but its use has dropped dramatically as using microform proved tedious for all but the devoted scholar. Over the years, the hum of the microfilm machine slowly went silent as digital media, born in the 1980s, began to replace it.

The aggregated microfilm collection, a physical format, was lost to the digital tsunami. The microfilm stations soon served only the most dedicated researchers at central locations such as Berea and the University of Kentucky. Further, students had no appetite or patience for microfilm. Microfilm lacked the immediate reward of instantaneous retrieval found in the more exciting original record or the more fluid digital record. And, many of the institutions were not willing to send original materials to Berea. Pine Mountain was one of those institutions.

But, of note, in the 1980s, microform had a good ability to live up to its “preservation” lifespan. As time progressed, it was lauded for its stability. It allowed the duplication of collections and the ability to provide a longer term of life for many poorly stored institutional collections. But, obviously, it is less than an engaging resource to access and has limited full use of the information. What it eventually did was to ensure that collections would become increasingly inaccessible and would continue to limit the ability to do comparative research with ease. As years passed, only researchers with both time and resources would travel and sit for hours with a microform reader.

Nevertheless, not having the advantage of the prescience of the digital revolution beginning in the late 1990s, microfilm was chosen for the 1980s SIA archival preservation project. It should be pointed out that the Society of American Archivists pushed these long-lived gifts into many collections with their microfilm campaign. The documents and “contact prints” that duplicated the original material allowed for “off-site” storage and brought many institutional holdings together in one location, such as the Berea College, Kentucky, repository for the SIA materials. The contact prints (copies) of the photographs in the institutional collections were used to create duplicate sets of the fragile photograph originals and were stored with the microfilmed documents at Berea, as well as copies given to the institutions that shared the photographs. This preservation effort was not in vain.

The SIA proposal was founded on sound principles of current archival practice and good preservation intentions, and most partners came to join the project. There were some partners, however, that were pushed into the collective effort, kicking and grumbling. Pine Mountain Settlement was one partner that did not meet the project with enthusiasm and pushed strongly against their inclusion in the project, initially declining to partner in the SIA project. [See NOTES]

The SIA correspondence regarding the Pine Mountain Settlement School institution’s eventual formal agreement or “buy-in” is a record of institutional anxiety on many sides. The University of Kentucky (UK) assisted in the collections transfer process. Kentucky had the equipment to manage the technical microform and film transfers. The copied material, microfilm, and contact prints of the photographs generated considerable debate. The photographs presented a point of concern as copyright concerns grew along with the new media. It was a concern at the core of the various visual collections and remains a concern today. Early on there was no formal accounting of how the images from the various institutions were to be used, even though standard attribution to the original institutions was closely followed.

Another loss for the original institutions and the researchers was the “go-to-place” experience. However, there were significant benefits to researchers who wished to study or compare and contrast multiple rural settlement schools. Berea wisely collected and joined additional original archival materials donated by various donors and resources. For many years, this collected body of SIA materials represented a central and “go-to” place for researchers interested in the Central and Southern Appalachians Settlement movement. The added collections and SIA archives were and are of value to researchers. The dilemma was access to the material for those communities responsible for the creation of the collections. The small institutions that had created the records of their history did not have direct management of their “story” under the new technology demands. The digital revolution has provided far more access, but less stability and now, today, AI has a new set of questions..

In the deep discussion that preceded the agreement of Pine Mountain Settlement School to participate in the SIA project, it became a highly sensitive topic in the Settlement School and researcher communities. Researchers, often overly dependent on the microfilm and the accompanying archival materials, clearly missed the essence of “place,” and few researchers had the patience to methodically move through reels of film to try to grasp the essence of a community. Compounding the research picture was the reluctance of some researchers to visit the Settlement institutions and which can be found in some of the shallow research derived from the troublesome materials and methods. Further, the Settlement institutions soon rarely ventured to Berea to go through their own microform holdings, creating a distance from the institutions’ history and the lessons of history. Also, new material related to the SIA institutions was most often directed to Berea, further fracturing the fabric of the local collections and archives from their origins.

However, it is important to note that the SIA institutions, such as Hindman and Pine Mountain Settlement, continued to accumulate records on site and, like Pine Mountain, their institutional archives did not end in 1983, but they continued to build on the returned original records and did not pursue further microfilming. Thus, since 1983, many of the Settlement School archives and Records collections have grown. Today, the condition and the scale of the institutional records of the original SIA sites vary, and their institutional records are stored (or not) under varying conditions.

PMSS Collections: Issues

The ARCHIVE at Pine Mountain Settlement School IS NOT just the surrogate special collection captured within the earlier microform celluloid and the contact prints. That collection is only a small fraction of the Pine Mountain Settlement School ARCHIVE.

Efforts to address collections gathered from 1983 forward are an important need still facing the School and many other partners. The need to re-house and organize those later records continues and is a critical need. It is the post-1983 collections that pose the greatest risks to collections. As the School hosts more reunions and more octogenarians want to recall their Boarding School years, and the younger generations in the Community want to fill in gaps in their family histories, the need to provide manageable, secure, and sensible access to the institutional records continues to grow.

Today’s records and property management do not fully acknowledge the collection context and its inherent issues. But then, the Pine Mountain Settlement School is an uneasy captive that does not easily yield up its secrets, joys, and sense of place. The Pine Mountain Settlement School archival materials at Berea were pulled from their original sites with good intentions, but the process was made uncomfortable from the beginning. The local correspondence suggests that the complexity of the SIA relationships grew.

Living history does not capture well in static systems. When history is asked to live within its surrogates of celluloid, zeros and ones, in multi-generation copy photographs, in tightly regulated boxes, and in closed shelves, it often struggles with identity. Yet, collections can also die from neglect, from being placed in a closed-door mausoleum or left to the elements and disorder. Institutional archives can suffer from a kind of cancer of abandonment from within when their institutions fail to recognize the need for responsible collection supervision of fragile materials on site. Archivists are few and far between. It is a special mania, or as some have said, a “fever” … but a good fever and one desperately needed in small collections and archives across the country.

The dilemmas inherent in the Pine Mountain Settlement School surrogates at Berea College and the complex and poorly processed and integrated ARCHIVE at the Settlement School present issues in any intelligent articulation of the Pine Mountain Settlement School community as it has grown.

With the rise of Artificial Intelligence, another iteration of collection management is on the horizon. How will new technologies capture and share the forests and the creatures, the arts and the crafts, the life and livelihood of the community, governance and administration, and the past and emergent arrangement of history? …. It remains to be known.

PMSS and Berea College

See Also: ARCHIVE 1983 PMSS Records on Berea College Microfilm

The following is Berea’s description of the Pine Mountain Settlement School collections held on microfilm at the College:

Restrictions: Records and photographs can be accessed through the Reading Room, Berea College Special Collections and Archives, Hutchins Library, and Berea College.

Rights: Regarding records contained in the collection:

Pine Mountain Settlement School records were collected and organized in 1982. Those having administrative, legal, or historical value were microfilmed at the Kentucky Department for Libraries and Archives and all were then returned to Pine Mountain. The resultant microfilm master negative is owned by Berea College. A user copy is available for researchers. Berea College does not own the copyright for the manuscripts or printed documents included in this microfilm edition. Therefore, it is the researcher’s responsibility to secure permission to publish from Pine Mountain Settlement School or its successors and assigns. Due to the personal information they contain, some records such as student and personnel records may be RESTRICTED.

Regarding photographs in the collection:

Pine Mountain Settlement School photographs were organized and copied in 1985. The copy negatives and a set of copy prints are owned by Berea College. A second set of copy prints and all originals were returned to Pine Mountain Settlement School. Permission has been granted by Pine Mountain Settlement School for Berea College to reproduce all or part of the school’s photographs and to use them in slide or film presentations, display them, or loan them for display, and to allow their use by researchers for reproduction and publication. The proper credit line for all of the above uses shall be, “Pine Mountain Settlement School Photographic Collection, Berea College Southern Appalachian Archives.” Records and photographs can be accessed through the Reading Room, Berea College Special Collections and Archives, Hutchins Library, Berea College. https://berea.libraryhost.com/index.php?p=collections/controlcard&id=42

THE PMSS ARCHIVE in Context

The standard film preservation practice of contact prints for photograph material and microfilm for documents has given the Pine Mountain Settlement School collections some security but it fails to place the history within its context — or context within its broader settlement institutional histories — depending on the vantage point. While the valuable preservation processes only scratched the surface in 1983-1984, they stirred up a rich soil that is the ARCHIVE of Pine Mountain now evolving and growing within a digital world. That digital world is a world that is redefining the archive and with it, “information” as well as preservation, conservation, ownership, and ultimately physical storage and on-site accessibility.

Claude Shannon, who along with Alan Turing, was a noted cryptographer and code breaker, told us long ago that “Information, though related to the everyday meaning of the word, should not be confused with it.” This can certainly be contemplated by collections gathered within their communities of origin. Information is, as our contemporary author James Gleick tells us in his book The Information: A History, a Theory, a Flood (2011)*, that information as an entity is “uncertainty, surprise, difficulty, and entropy.” These views describe many of the small local archives scattered throughout the world — and are suggestive of the enigmatic nature of the Pine Mountain Settlement School archive. It also describes the other Settlement institutions that joined Pine Mountain in the Berea College Settlement Institutions of Appalachia archive.

*[See: James Glick, The Information: A History, a Theory, a Flood, 2011]

At Pine Mountain Settlement School the deep forest, open fields, pristine air and water, the surrounding community with its sincere, bright, devotional, and struggling populations; the 24 buildings, stonework, trails, play equipment, cultural collections (most notably Native American artifacts and Pioneer tools), weaving, native botanical habitats, birds, treasured trees, etc.; the staff that annually hold programs regarding their care; and the many special events that stick to the visual and auditory memory of those who have stayed long enough to be captured by the magic of the place ——–this is what is hidden beneath the standard secondary descriptions of place. In reality, Pine Mountain is a place of notes hidden in walls, in boxes, in memories. The personal letters of students describing their educational experience, and the passionate letters of the defenders of Pine Mountain Settlement School experiences with “Lands Unsuitable for Mining,”, walks to Trillium Rock dressed in its annual spring-time garment, squeezing fat bodies through “Split Rock”, a child’s first glimpse of a beaver, or a dragonfly resting on the mossy rock of Isaac’s Creek, etc., etc. …..

In the deep and isolated valley sandwiched between two mountains, it is the undiscovered and implied information in the tangible that forms the deep definitions of place. “Place” is often filled with “uncertainty, surprise, difficulty, and entropy” A sense of place is what this ARCHIVAL RECORD attempts to capture and reveal and encourage. It is not just the structured list of objects, dates, names, deeds, photographs, and now media that one often finds in institutional and many online archives — (though there are many of those inscrutable works in the Pine Mountain Settlement School archive.) What sticks to the senses are the first-hand accounts and the stories that still abound in the School record. It is also the untold stories that happen when the environment surrounds and informs the written and photographed record.

The archival collection at Pine Mountain Settlement is an infosphere of collections. It is found in a multitude of dark or brilliant corners of personal lives that overlapped with the physical site of Pine Mountain Settlement School. It is where those with connections to the area may discover their own true nature and where an understanding of the Pine Mountain Settlement School community is uniquely and often privately revealed and where it resonates — for good or ill. No matter the place of birth, Pine Mountain Settlement is born of the community, but it is the community of us all. Telling the story of an institution, of a community as complex as Pine Mountain is not a tidy business … but, then, neither are our lives.

PINE MOUNTAIN SETTLEMENT SCHOOL Collections

The collections gathered by Pine Mountain Settlement School follow a selective process that sometimes aggregates in a seemingly arbitrary manner. This is in part due to the nature of collections when assembled and brought forward through the interesting discoveries of various keepers [archivists]. The keepers’ interests and their stories sometimes mingle and pull selected facts forward — as it should be. The Pine Mountain collections of letters, photos, poetry, and perfidery discovered in the collections display the stamps of eras, personalities, interests, politics, religious focus, etc. The collections also display attempts of the contributors to capture their common moments, their focus, their reflections, their memories, as they associated with the information and the institution. Sometimes the whole is a crazy quilt of the anguish and joy and pessimism and optimism of students of the Boarding School years and the Community School, past Directors at odds with staff, and volunteers, friends of the School, and interested visitors discovering unknowns and sometimes misrepresenting them. The many who have streamed through this remote corner of Kentucky have contributed to the many diverse and associated documents and to the institutional history of this unique place.

Much more remains to be discovered regarding the creation of the collections — the creation of the history of place. The journey of discovery has only begun to explore what is hidden in the memories, reflections, and even the fabrications of those who live and lived there. Archival collections are a fluid stream of history and story. We, the keepers of history, do not doubt that later discoveries will capture more enigmatic and individual adventures — more hidden history in this magical place that we have “cherry-picked”. In the first one-hundred-plus years, the gathering, re-gathering, and discovering that went into the collective archive all point the way to a myriad of stories, multiple definitions, and much greater understanding of a unique corner of Appalachia. But, the stories that each user finds in the ARCHIVAL collections are their discoveries and theirs to re-tell.