Pine Mountain Settlement School

Series : SCRAPBOOKS

Series 14: MEDICAL Health and Hygiene

SCRAPBOOKS

Strange Chronology of Disease

in the Pine Mountain KY Region

LOCAL HISTORY SCRAPBOOK 1920-1980 A Strange Chronology of Disease … in the Pine Mountain KY Region

A STRANGE CHRONOLOGY OF DISEASE AND DEMONIACAL POSSESSION

IN THE PINE MOUNTAIN, KY REGION

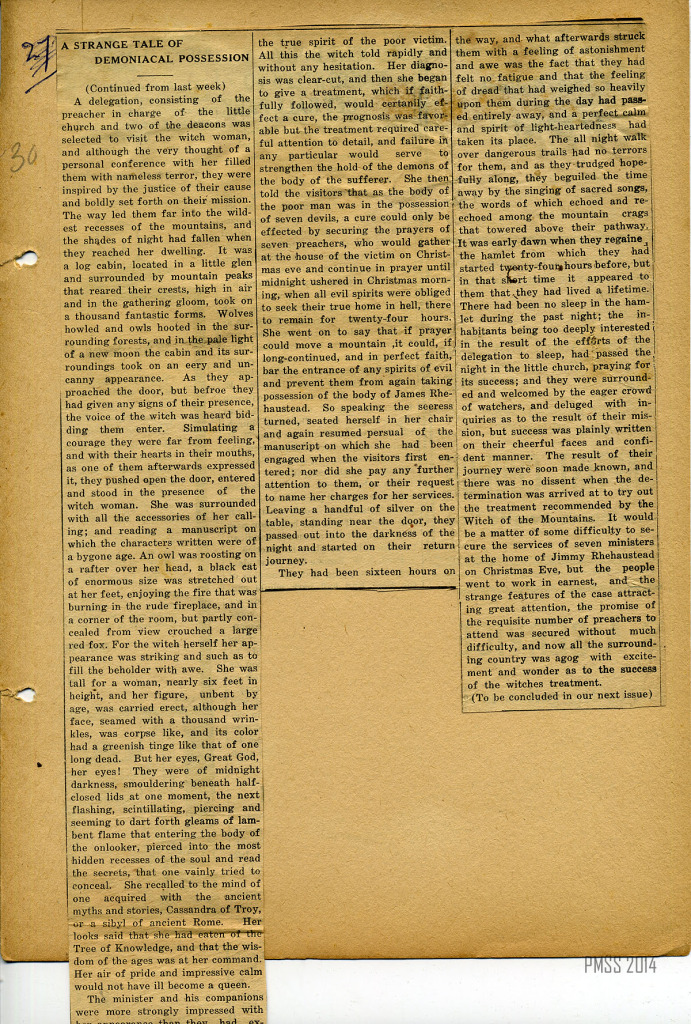

“A Strange Tale of Demoniacal Possession” [fragment from unknown news source], n.d. [before 1929] Page 27a. [local_hist_album_027.jpg]

TAGS: disease, medical conditions, demoniacal possession, newspapers, superstition, sensationalism, owls, black cats, Witch of the Mountains, Cassandra, Christmas Eve, 7 Preachers, 7 devils, medical history, Pine Mountain, Kentucky, Pine Mountain Settlement School, local history, New England, Anne Hutchinson, Puritans, witches, religion, John Dee, antinomians, John Winthrop, influenza, Diptheria, epidemics, tuberculosis, mumps, scarlet fever, measles, whooping cough, smallpox, typhoid, meningitis, trachoma

LOCAL HISTORY SCRAPBOOK A Strange Chronology of Disease in the Pine Mountain KY Region

“A STRANGE CASE OF DEMONIACAL POSSESSION” (newspaper fragment)

This fragment is part of a large Scrapbook [Local History Scrapbook] kept by Pine Mountain Settlement School staff in the earliest years of the School. It is a strange little piece that was no doubt related to stories that often circulated in the Pine Mountain Community and apparently throughout Appalachia. It is a story about an undiagnosed illness and witches and demons and people who could “cast spells” to cure the sick. It is too bad that only this small fragment remains of this curious story, but it is enough to intrigue and confirm the early local fascination with demoniacal possession.

It is not unusual to find this kind of tale appealing to local newspapers as the topic already circulated in the oral histories of the region. This fascination continues to push stories of similar content in today’s papers. The mystical un-explained, and witches, and demons sell newspapers and they still capture large audiences in today’s electronic media. But, we might learn more by asking what do historical records tell us about that appeal of the supernatural and that fascination with the “demoniacal” — as the author describes it? Does it still reflect our local or national state of mind? And, why?

THE TALE OF ANNE HUTCHINSON

Much earlier explorations of demoniacal possession can be found in the real-life tale of Anne Hutchinson. Her story is one of the earliest “witch” stories in our national history. It is a disturbing story that has caught the imagination of many who have read about her ordeal. But, earlier instances, just as disturbing, are also found in British medical history sources. There are many accounts of women accused of witchcraft if only because their status as healers gave them social power and that power was in competition with the local physician. The same was true of fortune-tellers. One particularly notable “healer” and astrologer, was the Anglo-Welch alchemist John Dee, (13 July 1527 – 1608 or 1609). Also a mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, teacher, and occultist, Dee was regularly consulted for medicinal remedies for a range of diseases and was regularly chastised for his esoteric beliefs, but he was also a man of repute when it came to the actual “healing”. He aligns with what was then most often called a “sorcerer.”

See: https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/king-james-vi-and-is-demonology-1597; Daemonologie 1603. http://www.gutenberg.org/files/25929/25929-h/25929-h.html

When John Dee’s Daemonologie was published in 1597 and released in England in 1603 it created sensation and controversy. It also set the stage for Anne Hutchinson’s ordeal in the New World of America. Yet, unlike Anne Hutchinson, he was not “excommunicated”, but had a substantial following of alchemists and physicians who kept him from the “dunking chair” but not from Church suspicion.

This strange little fragment in the news article seen above was not far removed from what has been called the Antinomian controversy surrounding Ann Hutchinson. Ann was a Puritan spiritual advisor, religious reformer, and a “healer” in the Massachusetts Bay Colony from 1636 to 1638. [Wikipedia] and when she pushed against the orthodoxy of the clergy in early Cambridge, Massachusetts, she was accused of heresy and was brought to trial as a threat to the religious stability of the Bay colony.

Anne was subsequently accused of witchcraft but what she appears to have violated was the male dominated religious theology of the Anglican church and its largely all-male clergy. In fact, as author Eve La Plante* describes her in her non-fiction account of Hutchinson’s life, the clergy “...suspected her of using her devilish powers to subjugate men by establishing ‘the community of women’ to foster ‘their abominable wickedness.” La Plant, in her book seeks to show Hutchinson, not as a witch, practicing “witchcraft”, but as a woman whose theology threatened the clergy.

Hutchinson had enormous command of the Bible and her power and knowledge of the Bible along with her medical aid, particularly in times of childbirth and grave illness, brought her the praise of women and also many men. In fact, her weekly meetings for local women to discuss scripture were soon joined by a growing number of men. John Winthrop, the reigning cleric of the local Puritans began to be threatened by Anne’s articulate interpretation of Biblical sources and the battle of theologies was joined.

- *LaPlante, Eve (2004). American Jezebel, the Uncommon Life of Anne Hutchinson, the Woman who Defied the Puritans. San Francisco: Harper Collins. ISBN 0-06-056233-1.

PURITANS AND JOHN WINTHROP

John Winthrop, the first Massachusetts Bay Company governor, called for a trial of Hutchinson in an attempt to subdue or at least reduce her growing influence as a healer and spiritual consultant in the community. It is from within Winthrops’ journals that Hutchinson and her life and trial give us a first-hand description. Eve La Plante describes Winthrop

[He] saw himself as the Moses of a new Exodus, embarking on a second Protestant Reformation — withdrawing from the Church of England as it had withdrawn a century earlier from the church of Rome. In the spring of 1630 he led a flotilla of eleven ships carrying nearly a thousand nonconformist Protestants like himself across the Atlantic Ocean. Unlike the Separatists who nine years earlier had founded Plymouth Plantation, Winthrop aimed not to separate from his country but to extend its reach while purifying its church — hence the name NEW England.*

*Le Plante, Eve. American Jezebel: The Uncommon Life of Anne Hutchinson, the Woman Who Defied the Puritans, New York: Harper Collins, 2004, p.5.

It all ended badly for Anne Hutchinson. La Plante says, had Hutchinson lived today she “might have been a minister, a politician, or a writer.” But even today the going might still have been tough, as it has proved to be for so many intelligent women who exemplify the American spirit of independence and who speak truth to power.

Anne Hutchinson, with no lawyer and no advisor and at the age of 43 and still nursing her 19-month-old child, Zuriel —the last of her 15 pregnancies — appeared on demand before her accusers. They told her that her healing and preaching actions were “not to be suffered for.” He further added,

“We see no rule of God for this. We see not that any should have authority to set up any other exercises besides what authority hath already set up. And so what hurt comes of this, you will be guilty of, and we for suffering you.”

LaPlante p.18

Shaky ground, indeed, with which to establish the New England of the New World, proclaimed the well-established clergy. This kind of religious debate was all too fresh and familiar to the Pilgrims and to all the growing body of so-called antinomians streaming to the New World from England — Diggers, Ranters, Shakers, and other sects, who today are often grouped under the title “Puritan.” The search of these dissenters was a search for religious freedom and that search was the cause that brought many of those persecuted religions to fiercely seek freedom of worship to the shores of New England only to find that dissent had also tagged along.

RELIGION AND DISEASE

So why does religious intolerance resonate so strongly with witches and the daemonic? What does it have to do with disease and medicine in Early America? What is the relationship to Appalachian medicine? The answer is subtle but also profound for those tracing the deeply rooted origins of many myths and stories that have grown out of the region. It sits embedded within the medicinal history of families who came into the mountains of Eastern Kentucky in the early 1700s. It is those vestigial remnants that from time to time bring writers to the region to test their theses and explore relationships with Merrie Old England. It is the history surrounding the early apothecaries of mountain healers, such as the one in this newspaper fragment. It also speaks to a lingering contestation regarding the “hidden” beneficence of the New England settlement workers on the “native” Appalachians. Or, as Samuel Tyndale Wilson, an early Presbyterian minister referred to the “natives” whom he referred to as “Appalachian Whites”. His reference to “Appalachian Whites” seems to ignore the history of early medicine in Appalachia which owes much to the Native Americans and later to the African Americans who brought native healing methods to the South. The exclusion of the two populations in early Appalachian history only added to the myth of the “witch healer”.

ANN HUTCHINSON AND THE NATIVE AMERICAN COMMUNITY

Following her husband’s death, Anne Hutchinson self-exiled from Cambridge and sought safety and refuge for her family in the Dutch colony of Pelham Bay, (now the Bronx) New York. Largely isolated from everyone but neighbors and family, Anne was nonetheless within her small community still championing religious toleration, and learning more about the skills of Native healers. However, her community was showing little regard for the rights of their Native American neighbors.

In February of 1643, in response to a surprise attack by the Dutch colony militia on suspected Indian raiders, the Siwanoy Indians began to speak of retaliating. In mid-July, the Siwanoy showed signs of carrying out their threats against the intrusive and often abusive settlers. Forewarned, most of the members of the Dutch Colony sought shelter. Anne, nonetheless, believing that her relations with the Siwanoy tribe had been good and were reliable, was one of the few families not to seek shelter. The result was tragic. Anne and most members of her family were massacred.* Anne was 52.

NOTE: Not all the family was massacred. According to La Plante “One little Hutchinson child [Susanna]— and the five older ones who were not present — survived. Among Anne’s descendents were Eva LaPlante, the author of the book American Jezebel and Franklin D. Roosevelt, George H. Bush and George W. Bush. [Wikipedia] Eight year-old Susanna Hutchinson captured by the Siwanoy Indians was held for approximately 3 years and then traded and released to the remaining family. While in captivity she reportedly had a son with the Siwanoy sachem Wampage I – Ninham, who would later become Wampage II. At the age of 18 she married tavern owner Samuel Cole and lived a long life and bore many children.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Susanna_Cole

Another scholar and historian, Andrew Delbanco tells us that Edward Johnson, one of her detractors, even after her death called her a more “cunning Devil than the Native tribes.” In a particularly cynical observation, Delbanco says that Johnson’s remarks exemplified that of other New Englanders and were said in order to “ratify its (New Englander) godliness. ” and

…that in order to ratify its godliness New England had to find its local Satans.” … Satan’s various forms were the “savage” Native, the Antinomian, the Quaker, and the “witch”.

Le Plante, p. 233.

All said it is a very sad tale in the end. Anne and her detractors had brought not only their religious battles and intolerance, but they also brought something even more lethal, European diseases. The lethal European diseases killed millions of Native Americans, and it is most likely that one or more of those diseases was responsible for the Indian burials under the so-called Indian Cliff Dwelling at Pine Mountain Settlement School.

The “witch” depicted in this newspaper fragment is both Satan and a Godly healer as insinuated by the author of the unknown newspaper fragment above. The Anne Hutchinson story and other similar antinomian scenarios embellish this complex dualism in much the same manner. The complicated but intriguing relationship of mountain religions with their deep New England Puritan roots is often a confounding story. Often the disparate benefactors and detractors of homegrown Mountain religious beliefs are lost in the sensational story of witches and demons. Too frequently these tales obscure or confuse any attempt to define or explain many mountain healers. Sometimes the confusion still spills over into the churches, and many times the strength of beliefs shapes the culture.

GERMS AND GOD

Germs and God can sometimes be given over to the divine or to the disease. The need for seven preachers to confront the seven demons suggests a need for balance in the story but also speaks to the magic of the number 7, But even more, it speaks to our need to explain our illnesses and our deaths. We also have been forced lately to wonder why the germ of an idea can transform into the germ of disease. The idea of “witch” as mediator then leaves open the questions — and there are many of them — who holds the power? The self, God, the unknown? No one. What is a witch? Why do germs kill some and save others? The early relationship of the Settlement School with its New England founders and workers worked uneasily within a land of witches and demons and germs and disease. “7 preachers for 7 demons” and a witch to run interference, all signal the persistence and the fascination of unfounded beliefs.

Today, some are left to wonder how much progress we have made in confronting our witches and our demons. What comes to mind, as well, is the violent death of Anne Hutchinson at the hands of the trusted Native Americans among whom she had chosen to live. Did the Indians bring their 7 to equal that of the Puritans? Did their Shamen require this retaliation? Would one life for another be enough? Where was the witch? The Shamen? Millions of Native Americans would die from disease while the newcomers to the New World executed their own because of their religious dis-ease. Could it be that the germ of an idea killed Ann Hutchinson and millions of Native Americans? Or was it the “germs” brought to the new land and no medical cures? Or, was it too much religion or too little? Did the witch keep the demons from the door and save the sick man as in the story’s fragment? In a land of disease, no one witch, or 7 preachers, 7 Native Americans, or ceremony, or belief system, will bring back the dead. We are left to wonder about this fragment of our history and who suffers the most from demoniacal possession/obsession, the dis-eased or the healer.

[*Transcription pending]

SEE ALSO

SCRAPBOOKS Guide

LOCAL HISTORY SCRAPBOOK Guide

SCRAPBOOK BEFORE 1929 Guide

LOCAL HISTORY SCRAPBOOK A Night of Horror…