Pine Mountain Settlement School

Series 10: BUILT ENVIRONMENT

National Landmark Designation and Obligation

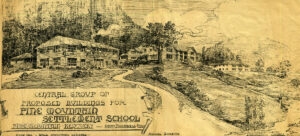

Mary Rockwell Hook, Proposed buildings for Pine Mountain Settlement School. Dining Hall, Girls Industrial Classes, School Building, ? Industrial, & Boy’s Classes, [1913 ]. [hook_Panorama2_edited-1]

TAGS: National Historic Landmarks, United States Department of Interior, National Register of Historic Places, nationally significant properties, National Park Service’s National Historic Landmark Survey, Women’s History Landmark Project, Secretary of the Interior’s Standards for Historic Preservation, Lands Unsuitable for Mining petition, preservation grants and loans, Save America’s Treasurers grant

PMSS NATIONAL LANDMARK DESIGNATION AND OBLIGATION

Pine Mountain Settlement School

History of Landmark Designation and Historic Preservation Obligations

by Karen Hudson (2019)

Pine Mountain Settlement School

Board of Trustees

General

In 1992, Pine Mountain Settlement School was designated a National Historic Landmark by the United States Department of Interior. Only the country’s most renowned historic properties are

designated Landmarks—Mount Vernon, Pearl Harbor, the Apollo Mission Control Center,

Alcatraz, and Martin Luther King’s Birthplace, for example. Landmark designation automatically places a property in the National Register of Historic Places; the official list of the nation’s historic properties worthy of preservation. While there are more than 90,000 entries in the National Register, only a small fraction, approximately 2,500, are designated National Historic Landmarks. For example, while Kentucky has over 3,400 districts, sites, and structures encompassing more than 42,000 historic features listed in the National Register, only 32, including the Pine Mountain Settlement School, are designated Landmarks.

How are National Historic Landmarks different from other historic properties listed in the National Register of Historic Places?

National Historic Landmarks are properties recognized by the Secretary of the Interior as

possessing national significance. Nationally significant properties help us understand the history of the nation and illustrate the nationwide impact of events or persons associated with the property, its architectural type or style, or information potential. A nationally significant property is of exceptional value in representing or illustrating an important theme in the history of the nation.

Unlike Landmarks, most properties are listed in the National Register for their state and local

significance.

[Did You Know? The National Register of Historic Places has 93,350 total listings, 1,824,802 total contributing resources, including buildings, sites, structures, and objects. Of those listings, 1111 were made in 2017 alone.]

The impact of state or locally significant properties is restricted to a smaller geographic area. For example, many historic schools are listed in the National Register because of the historically important role they played in educating individuals in the community or state in which they are located. Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas, however, is nationally significant because it was the site of the first major confrontation over implementation of the Supreme Court’s 1954 decision outlawing racial segregation in public schools. The city’s resistance led to President Eisenhower’s decision to send Federal troops to enforce desegregation at this school in 1957.

The process for listing a property in the National Register is different from that for Landmark

designation and different criteria and procedures are used. Some properties are recommended as nationally significant when they are nominated to the National Register, but before they can be designated as National Historic Landmarks, they must undergo additional evaluation by the National Park Service’s National Historic Landmark Survey, Advisory Board, and Secretary of the Interior. Some properties listed in the National Register are subsequently identified by the Survey as nationally significant; others are identified through theme studies or special studies.

2

Pine Mountain, for example, was listed in the National Register in 1978 for its local and state

significance, but in 1992 its national significance was identified by a group undertaking a

nationwide thematic study on women’s history. In 1989 the Organization of American Historians and the National Coordinating Committee for the Promotion of History entered into a cooperative agreement with the National Park Service to undertake a Women’s History Landmark Project. At the time, only about 3 percent of the approximately 2,000 National Historic Landmarks focused on women’s history. The purpose of the Women’s History Landmark Project was to increase public awareness and appreciation of women’s history by identifying significant sites and preparing nomination forms for NHL consideration. As a result of the study, 40 properties associated with women’s history, including Pine Mountain Settlement School, were officially designated National Historic Landmarks; many more were nominated but not approved by the Department of Interior. As a result, though it had been listed in the National Register of Historic Places since 1978, in 1992, Pine Mountain Settlement School was officially designated a National Historic Landmark; the highest honor bestowed upon an historic property by the Department of the Interior.

How does Landmark designation affect Pine Mountain Settlement School’s ability to make changes to the property it owns?

While the Secretary of the Interior encourages owners to use the guidelines offered in the Secretary of the Interior’s Standards for Historic Preservation, owners are under no requirement to follow the guidance. Property owners are, in fact, free to make whatever changes they wish to the Landmark as long as no Federal funding, licensing, or permits are involved (Pine Mountain’s history with federal permitting and funding will be discussed in the next two sections). However, the National Park Service periodically monitors the status of National Historic Landmarks and if it determines alterations to the property do not meet the Secretary’s Standards and have greatly impacted its historic integrity, it can choose to remove the property from the National Register and revoke its Landmark designation.

How does Landmark designation protect Pine Mountain Settlement School from impacts

due to Federally funded or permitted actions?

While a private property owner is free to make and changes they wish to their historic property, subject to the potential of delisting, there are Federal laws which regulate the actions of Federally funded or permitted projects. For example, many property owners of Landmarks and National Register properties have found Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act useful in ensuring that incompatible development projects or other actions funded, permitted, or initiated by Federal agencies are reviewed and modifications made when possible to avoid, minimize, or mitigate possible harm to historic properties. Examples of undertakings that would receive Section 106 review might include levee construction and other flood control measures that could destroy archaeological sites; construction of a new four-lane, limited-access road through a rural historic district; permitting for surface mining, especially surface coal mining; and demolition, alteration, repair, and rehabilitation of deteriorated homes in a historic neighborhood funded by Community Development Block Grant monies to local governments. The purpose of the law is to require Federal agencies to consider the effects of their undertakings on the nation’s historic properties. Once this has been accomplished, Federal agencies may choose to proceed with the

3

undertaking as originally planned, modify it to mitigate damage to the property, or not undertake the project at all.

In 2002, when a local mining company proposed to expand a surface coal mining operation

within a mile of the Pine Mountain campus The Kentucky Resources Council, with the support of Pine Mountain Settlement School, brought a successful lawsuit against the mining company under the Lands Unsuitable for Mining portion of the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act. Since the mining operation required a permit from the Kentucky Natural Resources and Environmental Protection Cabinet, the project required Section 106 review. After following the review process, the Cabinet declared the mining operations could result in significant damage to important historic, cultural or aesthetic values. The Secretary found the viewshed of the School property, including the trails, would be adversely affected by mining north of the Pine Mountain Overthrust Fault, and that blasting could damage historic buildings and could threaten the safety of staff and students, as well as interfering with the use of the property for hiking, nature study and school curriculum purpose.

The cabinet received 2,274 letters in support of the petition to declare the area around the school as unsuitable for mining, and 76 letters opposing the petition. The overwhelming public support was mentioned in the Secretary’s Order granting the petition. As a result of the lawsuit, the cabinet concluded that 2,364 acres of land north of the Pine Mountain Settlement School were unsuitable for all types of surface coal mining operations.

Are there federal funds available for preserving or protecting National Historic

Landmarks?

Limited Federal grants through the Historic Preservation Fund are sometimes available to

Landmark owners. State and local governments occasionally have grant and loan programs

available for historic preservation; these funds tend to be for small amounts. National Register

listing is typically a condition for receiving preservation grants and loans from Federal, state and

local governments as well as private sources. Some funding sources give National Historic

Landmarks higher priority for funding than other National Register properties. There are also

Federal income tax incentives available for donating easements and for rehabilitating income-generating historic buildings. Recipients of Federal funding, can be affected by the same Federal laws discussed in the section above.

In 2008, the National Park Service awarded Pine Mountain Settlement School a $138,575 Save America’s Treasurers grant. To qualify for a SAT grant, a property must be designated a

National Historic Landmark or listed on the National Register at the national level of significance. By accepting the grant, Pine Mountain Settlement School agreed that all rehabilitation work would comply with the Secretary of the Interior’s Standards for Treatment of

Historic Properties with Guidelines for Rehabilitating Historic Properties, and must be approved

by the Kentucky Heritage Council. In recognition of the federal assistance Pine Mountain Settlement School agreed to grant a preservation and conservation easement to the Kentucky Heritage Council, the State Historic Preservation Office (see attached).

4

The purpose of the easement is to assure the architectural, scenic, historic and cultural values of the Property will be retained and maintained substantially in their current condition for preservation and conservation purposes. This obligation requires Pine Mountain to maintain the property in accordance with the Secretary of the Interior’s Standards for the Treatment of Historic Properties with Guidelines for Rehabilitating Historic Buildings, and Standards for Rehabilitation. The attached Easement details Pine Mountain Settlement School’s responsibilities.

The Kentucky Heritage Council may enter the property at reasonable times to monitor compliance with the Easement and Pine Mountain agrees to submit the attached Easement change form for review before beginning any work on structures or landscapes.