Pine Mountain Settlement School

POST: DANCING IN THE CABBAGE PATCH

Sheep

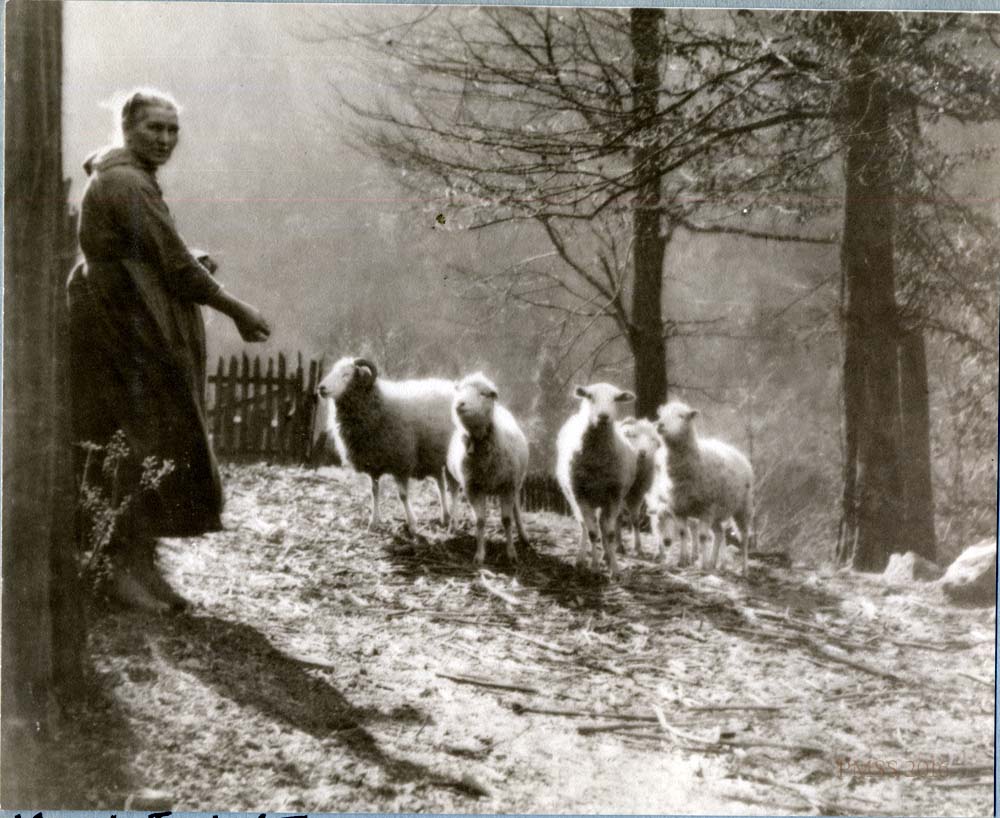

“‘Aunt Jude’ Turner, Big Laurel, about 1925” feeding sheep. [nace_II_album_010.jpg]

TAGS: sheep, agriculture, livestock, shearing, sheep shearing, wool, spinning, carding, weaving, dyeing, shepherds, textiles, looms, pastures, mutton, Thomas D. Clark, Aunt Jude Turner, Southeast Kentucky Sheep Producers Association, Patrick Angel, Merino sheep, Shetland sheep, Kentucky Sheep and Goat Development Office (KSGDO), Sarabeth Parido, sheep consultants, The Woolery

SHEEP

“The hills shall skip like lambs,” she sang

Of the mountain scallops ‘gainst the sky engraved.

Anew with gushing torrents laved

Were the mountain sides, and gay

With sarvice and red maples braved.

Sarah Marcia Loomis, Staff PMSS c. 1928

SHEEP THROUGH THE YEARS

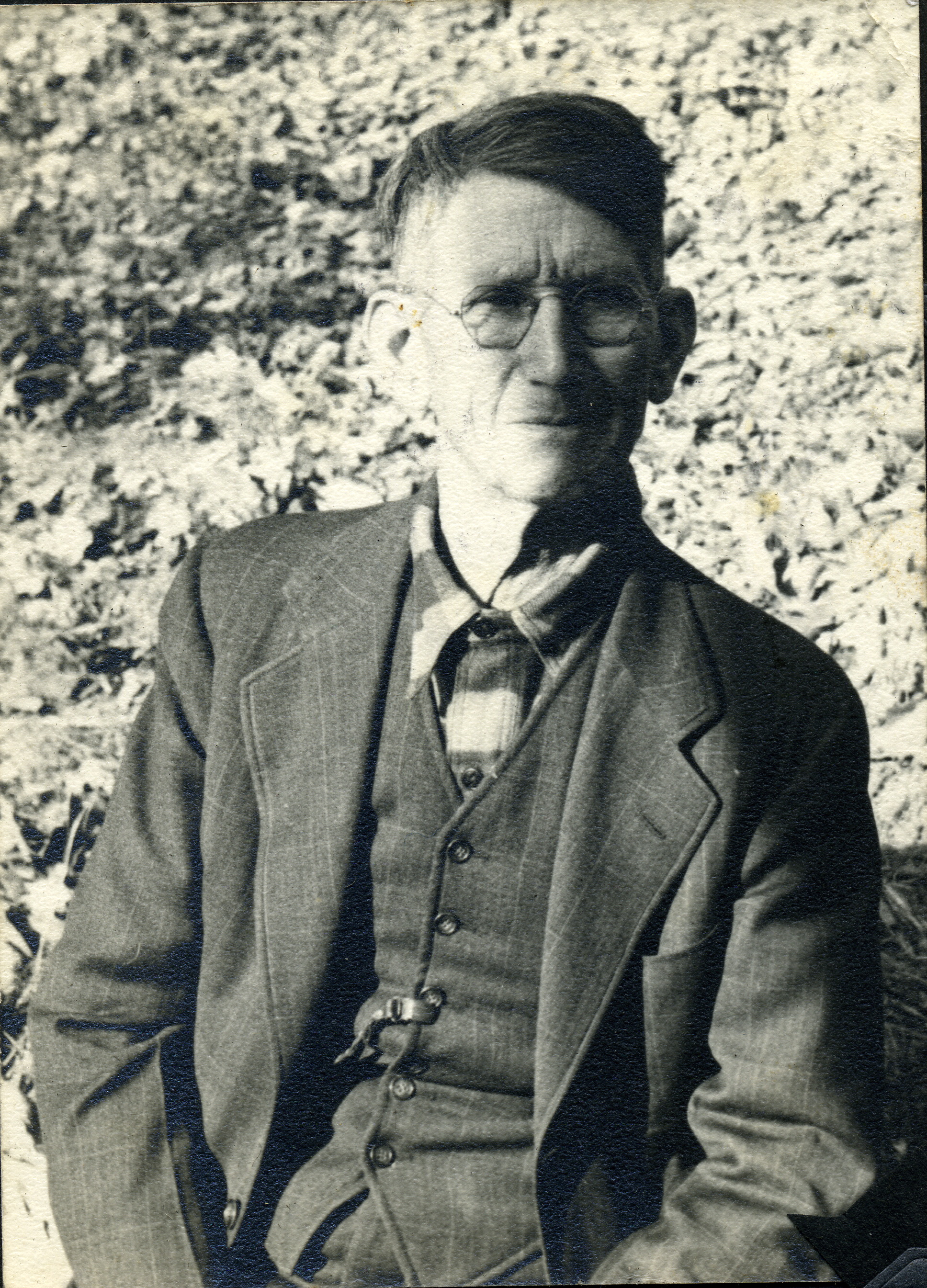

The photograph of Aunt Jude Turner feeding her sheep, seen above, is one of the most iconic photographs in the Pine Mountain Settlement School collections. Scattered throughout the early photographs taken at the School there are images of sheep, suggesting that they were an integral part of the landscape and life in the early years of the north side of the Pine Mountain. This image captures the essence of “romantic” sheep raising. But, was it all bucolic?

Bucolic, serene, and pastoral, are all words often used to describe sheep at pasture, Sometimes these words are found on early Pine Mountain Settlement photographs or on notes that refer to them. These are words that conjure up years gone by and times when many farms in Kentucky had flocks of sheep. But how many sheep were there? And, where do sheep figure into the agrarian life of Kentucky, and particularly into the life of eastern Kentucky? A historical review is revealing and surprising.

THOMAS D. CALRK AND Agrarian Kentucky (1977)

Thomas D. Clark, one of the most esteemed of Kentucky’s historians tackles some of those questions in his small but important book, Agrarian Kentucky, (1977). He tells us that

“The rolling country hills and valleys of Kentucky present a massive and alluring canvas. Dotted with peaceful farmsteads and modest cabins, the land collectively represents the substance and spirit of home. Its rurality has been the womb of a nostalgic history into which Kentuckians have often retreated …

Clark, Thomas D. Agrarian Kentucky, University of Kentucky Press, 1977, p.x. (Kentucky Bicentennial Bookshelf).

Clark’s history of Kentucky’s agrarian past can be eye-opening to those who choose to only give singular recognition to one Kentucky herbivorous animal — and that, the horse. The Kentucky horse was important, but what Clark makes clear in his little book on agrarian life is that along with the horse came a myriad of other farm animals that formed the backbone of rural life and, ultimately, industrial life in early Kentucky.

Agrarian Kentucky Clark tells us, is much more complex than the culture that has grown up around horses and crafts and memories of early pioneers. The common cattle, turkeys, hogs, chickens, goats, and sheep followed the early pioneers as they wagoned — or walked into the western wilderness. Often with possessions slung across the back of a horse or mule, the early pioneers traveled down the Great Wagon Road that ran through the Shenandoah Valley, and as they looked out on the great virgin forests of North Carolina, the great green valleys carved by meandering rivers in southwestern Virginia, and the vast game-lands of what was to become Kentucky, it must have looked like paradise.

As the migrations of settlers and their livestock increased into North Carolina and then back up to southwestern Virginia and into what is now eastern Kentucky, the pioneers were awed to see a wilderness dotted with herbivores —with buffalo, deer, and herds of elk. As they crossed over the Cumberland Gap and the mountains opened gradually into plains, there were even larger herds of buffalo and elk. It was a land ready for settlement and herbivores of all varieties.

What is little recognized is how quickly non-native farm animal species of almost every variety flowed into the state following the early arrival of the pioneers. Large numbers of European sheep were among the earliest arrivals. The livestock that came down the Wilderness Road and on the many flatboats floated down the Ohio was not a trickle. It was a torrent. The animals came, into the broad, sweeping landscape of Kentucky and they quickly adapted and grew strong.

As the pioneers settled in they added the animals that had remained for many of them a part of the nostalgic and bucolic memories of their life in other times and other countries. As wealth began to grow, the animals they owned became, for the settlers a symbol of new-found wealth in a conquered paradise. The scrub cow, mule, nag, sheep, and goats thrived on the lush forage of Kentucky. The evident health and strength of the animal caught the imagination of the early pioneer and began to give way to a sensitivity to the breed of their animals. Breeding began to grow in importance, and with it, the ferocious art of livestock trading.

The many early settlers who came down the Ohio on their flatboats also floated their sparse but precious cargo on the Kentucky, the Cumberland, and the Rockcastle rivers in the mid-eighteenth century. One of the earliest incursions was that represented by the party of the pioneer settler Benjamin Logan, known as “St. Asaph.” He settled in the area of Stanford, then called Logan’s Fort, in what later became Lincoln County. The year was 1775. The later settlements of Lexington, 42 miles north, and Somerset, 32 miles south, placed Logan’s Fort in a critical position for shaping agrarian practice in the heart of Kentucky’s lush grasslands — the Bluegrass.

THE WILDERNESS ROAD

A second route of the pioneer into the wilderness of Kentucky was along what is now known as the Wilderness Road. This primary “road” followed the well-used Indian trails that came from Virginia and that passed through the Cumberland Gap where Kentucky now touches the border of Tennessee. It is this more southern route that is central to an understanding of the early Central Appalachian pioneer family. This growing population of both early-comers and late-comers found the close mountains and private lifestyle of the terrain comforting — and cheap. They comprised the early settlers of eastern Kentucky and it is not surprising to find names today of the common ancestor who first settled the land. Nolans, Turners, Metcalfs, Boggs, and others formed a closely bonded origin and lifestyle. Sheep were very much a part of their history.

The Wilderness Road was the route taken by Daniel Boone and his party that eventually led the famous party to their settlement at Boonesboro Fort on the banks of the Kentucky River. When Daniel Boone and his party settled into Boonesboro Fort, it was the same year that the Benjamin Logan party settled near Stanford, or Logan’s Fort, not far away. The magical year for both was 1775.

These two 1775 primary settlements introduced many of the herbivores that became an integral force in growing Kentucky agriculture and that today continue to be foundational to farming in Kentucky. For example, the number of livestock accompanying the early migrants was generally dependent on the number of family members. Historian Clark gives us an interesting formula for dependency. He tells us that a family of four would most likely have brought with them, “... a horse and a mule, a bull, three cows, a ram and three ewes, four boars, five sows and fifteen pigs, a rooster, and two hens.” This estimate is based on what is known about the settlement patterns of the earliest pioneers. But by 1860, this generous allotment of livestock per family of four (an uncommonly low number for Kentucky families of that time) was curtailed by the dwindling supply of pasture. The decrease in pasture, says Clark, changes the estimated distribution of livestock to the family size and is far less generous. He writes

In 1860, by comparison, 21 persons would have had to depend on a horse and a mule; 6 1/2 would have looked to a single cow for milk; 2 would have had a single pig to satisfy their needs for pork; and 1 1/2 persons would have fared better sharing a single beef cow.

Clark, Agrarian … p.37.

However, not all things were equal in the early settlements when it came to sheep. Clark fails to mention sheep in the 1860 picture. By that year the gentle herbivore had already run up against some obstacles. The pioneers who took up settlement in the mountainous regions of eastern Kentucky soon found that sheep needed extra attention. Unlike the hardy hogs that were left to their own devices to forage, mate, give birth, and fatten, did not easily fill the smokehouses of the settlers. The sheep were higher maintenance. They needed to be monitored and protected from cougars and other predators, particularly the growing packs of roaming settler dogs that found the docile sheep an easy target. Further, there were few flat grasslands in the mountains and the uneven uncultivated terrain readily grew the most bothersome cockles, briars, beggers lice, and many prickly burrs that tangled the rich fleece of the sheep and refused to be easily coaxed from their thick coats.

Nevertheless, the early pioneers of eastern Kentucky persisted. While they reduced the number of sheep in their flock according to their household number, they did so thoughtfully. They often measured the flock number against the amount of wool that might come from each sheep sheared and how much could be traded and how much spun into wool for their large families. They grew adept at determining how many skeins of wool could be spun from the pounds of wool on each sheep. It was estimated that one adult sheep could produce about twenty pounds of fleece. It was a good educational mathematical exercise the maintenance of their household “budgets.” It was this simple mathematical formula and others that pointed to a growing disparity in agrarian practice in the two states of Kentucky. Geography had begun to define the distribution of agrarian wealth throughout the Blue Grass and in the eastern regions of Kentucky and it was increasingly uneven.

IN THE 19th CENTURY

While the migration of early settlers had slowed by the turn of the nineteenth century, the traffic across the Cumberland Gap had picked up. But, this traffic was largely going East. The new Eastward traffic was the surge of drovers pushing their livestock along the Wilderness Road to a growing livestock market in cities such as Philadelphia, Baltimore, Richmond, and south to Charleston. It’s estimated that while both the eastern mountain migrations and the Blue Grass migrations of settlers were staggering in their rapid rise during the last half of the eighteenth century, the livestock traffic exporting out of the two areas until the middle of the nineteenth century, was far greater.

Pioneer migrations clearly shaped the future of domestic herbivores, while they also reflected the role that choice played in the formation of distinct cultural lifestyles in Kentucky. The introduction of domestic herbivores into Kentucky defined the two migrant cultures. Where the two cultures met was in their adept dialog at “horse-trading.” The success of both highlanders and lowlanders in managing their livestock wisely and becoming clever “horse-traders” and drovers, kept agrarian life vital in the Blue Grass and all along the Wilderness Road for well over a century. The vibrant trade in livestock was an economic stream as critical to the economy of Kentucky as was the later lumber and coal boom. In the two latter economies, eastern Kentucky excelled…. and not. Neither coal nor trees could quickly be replenished in the market.

Yet, not all was rosy in the livestock trade, either. Thomas Clark, tells us a cautionary tale about the meteoric rise of the Kentucky livestock trade. He describes what he calls the “greatest tragedy” of the boom in livestock production in Kentucky. That was the tragic loss of the state’s lead in sheep production to the poor control of vagrant dogs. It was a loss of control that was both a civic and a political tragedy.

The story goes that because of the dominant political party’s fear of alienating their voter base, legislative action to restrain canines from marauding sheepfolds was never taken. The dogs won over the sheep. Today we train dogs to watch over sheep and goats, but in the earlier years, dogs often ran wild in a pack, much like wolves, that were even more destructive. During the early eras of Pine Mountain Settlement School, the various Directors struggled with similar agrarian tragedies. The early agrarian tragedies were also educational tragedies.

FARM LIFE IN THE PINE MOUNTAIN VALLEY

When Uncle William Creech married Aunt Sal in 1866 they struck out on their own to shape a life for themselves in the Pine Mountain Valley. Like so many pioneers before him, Uncle William brought the necessary sheep along with his new family to the Pine Mountain Valley. Uncle William wrote about the early years in his brief autobiography

“I will now get back to my subject of farm work. So early the next spring my wife children and myself went to getting ready for another crop, them to burning logs and brush and me plowing the ground and planting corn, which we worked hard until the first of August, Clearing land was the greatest industry for the fall and winter for several years until we had enough for what we needed for wheat, corn, rye and flax and buckwheat. In the dry season of the year we had to grind our meal on a hand mill which was very hard work. By raising flax and sheep my wife carded and spun and wove cloth to make clothes for us all while I tanned leather and made all the shoes that we wore. While the days was warm and dry we plowed and hoed corn and wet days and by night I worked in my blacksmith shop and my wife knit and spun. But when the children got large enough to do work the boys helped me and girls helped their mother. But all worked to gather in the cornfield.”

William Creech. A Short Sketch of My Life, after 1913 (written for Ethel de Long)

It is education we now know to be the backbone of successful agrarian practice and few schools have worked harder to integrate the two. At Pine Mountain Katherine Pettit, one of the co-founders of the School, shaped the idea of agrarian training as a kind of “Industrial training” in which she championed both formal education, civic education, and indirectly, political education. In her agrarian “classroom” she aimed to take her passion for the agrarian life and shape students into new citizens who could help shape a new social and civil society in the mountains. Agriculture was a persuasive model and not, as some have claimed, a prop for a cultural agenda. Like the later Ayrshire herd, sheep make for beautiful pictures, but farming sheep and milk cows makes for a marvelous education.

Pettit has been accused of being driven by her cultural interests and her desire to foster cultural programs at Pine Mountain to the exclusion of other needs at the School — particularly agricultural needs. Certainly, weaving and Appalachian weavers were never far from Pettit’s eye, but it was the land and its agricultural and educational potential that drove the bulk of her agendas.

“KIVERS”

In her quest to understand the richness of the Central Appalachians, Pettit discovered “kivers” and they became the focus of her collecting instincts. In a personal letter that Pettit wrote to a friend in 1911, she outlines her fascination with “kivers,” the woven bed covers, the products of many mountain looms. Generally woven of wool raised by the family, spun, and then dyed with natural plants, these “kivers” or coverlets were prized possessions in the mountain families. Katherine Pettit had a passion for “kivers.” She certainly traveled miles to go see and seek her “kivers” but it soon became the “kivers” connection to the educational process of arriving at a “kiver” that held her attention and later her crusade. In instinct, she was a farmer in training and an educator before she was a collector.

… we had to hurry up to the head of Greasy to see Mrs. Shell and her coverlids [weavings]. She is over sixty years old and had just finished shearing her 100 sheep. Then we walked four miles along the foot of Pine Mountain down to Mr. [William] Creech‘s where they had looms, spinning wheels, hackles, etc., and had been longing for years for somebody to come along and tell them where they could get some flax seed to plant. They had been hoping for a school for 30 years and offered 100 acres of land.

Page 8 – [1911_pettit_ltr_0008-1.jpg]

Evelyn K. Wells captures another part of the Pettit-sheep story in a letter home to her family in 1918, in which she again describes the Shell family

https://pinemountainsettlement.net/?page_id=56474 Picture of Shell sheep. Sheep eating neighbor’s corn … “The other day I called on Aunt Sis Shell [Mary Elizabeth Nolan Shell]. She took me into the bedroom to see her wool, the fleeces of 50 sheep, black, Southdown and white, piled high on three feather beds, we have picked out some fleeces — mine, a lovely Southdown, gray-brown, to be woven into a linsey skirt for next winter.”

EVELYN K. WELLS 1918 Excerpts From Letters Home.

Writing to her family two years earlier in 1916, Evelyn Wells again singles out the Shell family whom she had just visited and suggests that not all sheep farming was bucolic. She describes the visit, “He was most entertaining, telling us all about the game one used to be able to catch, and conditions when the country was really wild.” ….. Later, in her letter, she describes another visit to the Shell home where

“I saw a quaint procession passing, through the bottomland. Aunt Sis stalking along, behind her Uncle John with his beard and slouch hat, and after them a boy driving a sledge drawn by a team of oxen. They are getting in their corn because the sheep are eating it….”

EVELYN K. WELLS 1916 Excerpts From Letters Home.

It is the agriculture that sits behind each “coverlid” that became a primary concern to Pettit and her community of subsistence farmers.

SHEEP ALONG THE PINE MOUNTAIN

Kingman Album. Woman with sheep following her. [c. 1920’s] [kingman_021d]

The raising of sheep and the issues of negotiating the open pastures in the first decades of the twentieth century were a source of constant contestation. Usually, disputes were worked out neighbor to neighbor but sometimes — not. Pigs were of the greatest concern as they were often the most destructive farm animal on the loose. Sheep, it appears, could also create issues, such as foraging in a neighbor’s corn patch. One story relayed by Pine Mountain staff member Alice Cobb describes the common incident in which sheep eat a neighbor’s corn crop.

Another incident, also described by Alice Cobb in her brief vignettes of life in the Pine Mountain valley, is more serious and ends up in court but as the incident is re-told it becomes a story of “clever justice”.

All evidence in the Pine Mountain Valley shows that the raising of sheep and the shearing of the sheep for wool was persistent and intermittently practiced in dwindling numbers until the late 1980s. Again Pine Mountain staff member Alice Cobb describes her observations as an “outsider” of a household that is “too evasive to be captured”

There are fifty million “schoolhouses in the foothills” stories to be dramatized, published, gobbled and washed down with laughter and tears. The truth is that the situation is too evasive to be captured except in a net of romance or a mire of realism, and every small incident has its share of both. We from the outside come down to the hills. Many of us see the quaint picture of Mag shearing her sheep and spinning the wool, Grannie Hall dipping vegetable dyes and weaving rare patterns in rare colors; ….

Alice Cobb, Letters

What Cobb does in her insightful and graphic descriptions of life in the Pine Mountain Valley is capture and explode the romantic notion of culture as a singularity only recognized in the photograph or romantic or picturesque story posed to inform the outsider. What she draws our attention to is the pervasive and often grinding agrarian labor of most all life in the Pine Mountain Valley. The multitude of hours it takes to raise sheep, goats, and cows; the back-breaking labor of farming a steep hillside; the desire for education that is devoured by the hours at the simple tasks of making a life. Maintaining a mountain home is an education, but not of the schoolhouse type. The maintenance of that education was not bucolic or picturesque until its conversion into memories and reverie.

The tasks associated with an agrarian life are labor-intensive and demanding on every member of the family. A subsistence farm is not so much a culture as it is a composite of the family’s relationship to the land, their husbandry of their animals, and their household skills in managing their small plots of land and large families. An agrarian existence is often centered on the success or failure of the agriculture skill of the family. The enhancement of this life and the preservation of the memories were at the heart of Pettit’s mission. The “kivers” were her “school books”.

Even earlier, in 1911, three years before Pine Mountain was founded, Katherine Pettit and a large group from Berea traveled to eastern Kentucky. A companion on the journey, Maria McVay [McVey ?], described the trip in a serialized diary published in a major Cincinnati newspaper. Pettit mentions the trip briefly in an early 1911 letter to potential donors for a new mountain School in Harlan County. Written while she was still at Hindman she recalled her first impression of the mountainous eastern region.

Writing from Hindman, she describes the life of families in the Pine Mountain Valley that she witnessed on her very first long trip to the region in 1899. With that group gathered by Berea faculty member Henry Mixter Penniman and other travelers, she was clearly moved by the beauty and the deprivation of the area. Surrounded by kindred spirits, including the suffragist Madeline McDowell Breckenridge,, and the outspoken geographer, “Nellie” Semple [Ellen Churchill Semple], who all had their views about the skills of farming, Pettit began to shape her plans for a school in the Pine Mountain valley.

In her Letter to Friends, she describes the remote valley and with a reflection of deep regret, she also describes the push and pull of industrialization that was manifested in the railroad then entering the mountains. In an effort to prepare mountain communities for the coming industrialization, she began to form a vision that would take native craft and mix it with informed industrial training and traditional educational coursework much like the program she had initiated at Hindman Settlement.

Pettit writes

” …. we had to hurry up to the head of Greasy to see Mrs. Shell and her coverlids [weavings]. She is over sixty years old and had just finished shearing her 100 sheep. Then we walked four miles along the foot of Pine Mountain down to Mr. [William] Creech‘s where they had looms, spinning wheels, hackles, etc., and had been longing for years for somebody to come along and tell them where they could get some flax seed to plant. They had been hoping for a school for 30 years and offered 100 acres of land.….

While we were lying there in those cliffs, looking up at the sky and the eagles soaring above us, we heard the whistle of the locomotive and then [(strike through) our guide] Christopher Columbus [Creech] told us it was the first passenger train going up the Cumberland River twenty miles above Harlan Town to Looney Creek on the Black Mountain and Wasioto Railroad. You can imagine the shock I had when I realized that near this remote mountain region where I stood twelve [(striike-through) eleven] years ago was the railroad.

Katherine Pettit. Correspondence n.d. (describes an 1899 trip) https://pinemountainsettlement.net/?page_id=39951

There, on that mountain cliff, it seemed, the dream she held for the region merged with that of Aunt Louize in Sally Loomis’ poem, Neverstill, “The hills shall skip like lambs,” she sang —- Of the mountain scallops ‘gainst the sky engraved.“

SHEEP IN THE PINE MOUNTAIN VALLEY

Along the Pine Mountain valley sheep were found on many early subsistence farms. In 1918, there is evidence that the Shell’s relationship with sheep was one that was long and deep as found in their knowledge of sheep raising and of weaving. It is probable that the Shell family had one of the earliest sheep flocks in the Pine Mountain Valley.

Emblematic of the return to models of an earlier time was the institution of the Community Farmer’s Day, later called “Fair Day. ” It was a day when the community could come together to show their skills in agriculture practice and animal husbandry. Community Day (Fair Day) was a time when students competed for prizes as the best hog-caller, and, yes, sheep-caller. Fair Day is a day that is still celebrated at Pine Mountain. Does anyone know how to call a sheep, today?

“How many of you ever heard hog calling? After some persuasion by Mr. Morris, the audience warmed up to the occasion and, with Old Aunt Till leading, half a dozen, one of them, little four-year-old Barbara Wilder [Brit and Ella Wilder’s daughter], filed up onto the porch and called the hogs or called the sheep, each in his or her own peculiar idiom. I know now why Mrs. [Alice Joy] Keith, when she first came, wondered what that train was that whistled down the valley at a certain time early each morning.” Community Day 1938

https://pinemountainsettlement.net/?page_id=46476

The stories of farming sheep were not all joy and bliss. At Pine Mountain, the stories of dogs and sheep also took a darkly humerous turn in a well-known local feud. The story of that feud told by staff member Alice Cobb is about the uneasy relationship of dogs to sheep and the “price” paid for allowing one to dominate the other. Alice tells of an incident in the Pine Mountain valley that resulted in a trial and a long-lived but — on the face of it — amusing animosity. The story revolves around the famous trial of Jim Boggs’ dogs killing Abner’s (Abner Boggs) sheep) https://pinemountainsettlement.net/?page_id=49255

Bish is the father of Jim Boggs [see Boggs Family], whom we visit at Turkey Fork occasionally. One time I asked Jim what relation he was to Abner, and he said, “He’s my half uncle, but we don’t claim no kin”. That was my first realization that the disagreement was really serious, so after that I avoided the subject in both homes. But the other night Abner brought it up himself. He asked me if I read the papers, and I confessed that I didn’t as much as I should. “Well,” he said, “Miss Cobbs, you’re going to be a reading even in the Indiana papers, some of these days, about little old Abner Bogg a shootin’ Jim Boggs. Cause as sure as that feller steps acrosst my paths a aimin’ to inconvenience me, I’m agoin’ to take a shot right for his heart. Of course I wasn’t alarmed, because Abner wouldn’t hurt anything — he just talks all the time. But he went on to tell us about the famous dog trial at Big Laurel, which seemed to be one of his quarrels with Jim. It seems that Jim’s dogs had killed Abner’s sheep — at least Abner thought they had, and he went and got a warrant, and arrested the dogs, brought them up to Big Laurel to the magistrate (that was Clarence Patterson), and they had a trial, with Bish Boggs, Silus [Silas ?] Turner, John Lewis, and someone else as the jury. Well the end of it was that they indicted the dogs for murder, and the jury voted for them to be sentenced, and then Jim Boggs went over to Harlan and got himself appointed a Deputy Sherriff and that gave him some influence with Clarence Patterson, and so the dogs were let out on good behaviour, and Abner’s lawsuit came to nothing.

Now if that isn’t real artistry, I don’t know what it is. Nobody but Abner Boggs would have had sufficient imagination to do a thing like that — he is truly an artist.

ALICE COBB STORIES Farewell Trip to Line Fork June 14, 1937 https://pinemountainsettlement.net/?page_id=49255

AGRARIAN-INDUSTRIAL EDUCATION “Sheep Calling” and the Community Fair

How did Pettit’s vision of a new agrarian-industrial education in the mountains begin? It began with an old set of customs married to a new and human-level industrial vision and idea in the mind of the Pettit, her co-founder, Ethel de Long, and her mentor, William Creech. Agriculture was an opportunity for social reconstruction and if a cultural re-birth of skilled craft could be interwoven — all the better. Agriculture and the raising of sheep were given a fervent push by the forceful personality of Katherine Pettit and those who were inspired by her and who followed her.

In 1941, the announcement of the Community Fair called forward a past more than a century old and a past that had a tradition at the Fair. But one that held promise for future centuries.

ANNUAL COMMUNITY DAY TO BE HELD OCTOBER 11 — HOST JUNIOR CLASS to dance and sing, eat ice cream, watch the set running and dramatization, practice sheep and hog calling; hosted by the Junior class; entertainment by five rural schools in the surrounding community. “Pine Mountain is keeping alive folk ways that are in danger of being lost or forgotten in the swift pace of the machine age, which is even now finding its way into the most remote sections of the Kentucky mountains.”

Volume 6 Pine Mountain Settlement School, September 1941

Harlan County, Kentucky, No. 1

As they did so many times, Pine Mountain looked to earlier practices of agrarian ways to enhance their current practice and to offset the growing cultural, social, and environmental impact of coal mining on the region. During both wars coal mining camps were springing up all over Harlan County and in the surrounding counties. Enormous loads of coal and young men were leaving the mountains to satisfy the war need. The reference to “machine age” is an indirect reference to a pre-war popular book by Malcolm Ross, The Machine Age in the Hills, 1933 — a favorite of Glyn Morris, director during the 1930s and early 40s.

While the School was lamenting the passing of earlier times and struggling with the ravages of mining, the number of sheep in Kentucky had been growing. The 2013 issue of the UK School of Agriculture Magazine, “No Business Like Sheep Business,” tells us that in 1942 the number of sheep in Kentucky had grown to over 1.4 million sheep. In the United States, there were 56.2 million sheep. Kentucky held the record for the most sheep per square mile of any state east of the Mississippi, according to the article.

THE PINE MOUNTAIN SETTLEMENT SHEEP EXPERIMENT

Malcolm Army’s grandsons, Michael and Eric with Burton Rogers and the sheep, 1980s. Photo courtesy of Suzanne Arny Fullar. [pmss_archives_arny_ photo1.jpg]

In the early 1950s there was an attempt to bring sheep back to the Pine Mountain Valley at the School. Sometime in 1953-54 a small flock of Merino sheep was purchased and was placed in the fields of the school. The Ayrshire herd had been sold and five beef cattle were purchased and they accompanied the sheep. The long-time farmer, William Hayes, had moved across the mountain to a new job as the Forest Ranger for the Kentenia Ranger Station and Brit Wilder, who carried many responsibilities on the farm, was assigned as acting head of Maintenance and the direction of the reduced farm. Brit was given sheep duty.

The School was slowly adjusting to cooperation with Harlan County Schools in the new Community School and everything was focused on making that educational experience work and the livestock were not high on the school’s radar. Pulled in many directions at once, in 1958-1959 the pilot trial of sheep at Pine Mountain ended, most likely due to the over-extension of staff to provide for their care. Brit Wilder was clearly over-committed by his responsibility to the farm and to maintenance.

In the 1970s there were intermittent attempts to bring back sheep and to re-focus on weaving. The period was marked by brief programs as the School that attempted to integrate sheep into the new Environmental Education offerings, Further, it was believed that the sheep could add to the new community Intervention program which also used weaving as an integrated part of its educational programming. It was during this time that community artisan, Sarah Bailey, led the School back to sheep.

SARAH BAILEY

Sarah Bailey was one of the most dedicated of the later crafts persons to work at the School and her efforts to bring natural dyeing back to the program and to maintain a weaving studio is fondly remembered by those who were privileged to work with her. Her full biography charts the important work she did for the School and chronicles her deep commitment to the craft of weaving and so many other mountain crafts. Her recommendations for a craft program are sound and still consulted but her reflections on sheep are not known.

SHEEP and PINE MOUNTAIN TODAY

Sheep have again entered into the Pine Mountain Settlement School conversation. Under the new direction of Preston Jones, the School has re-focused on the richness of the School’s agricultural heritage and married that to his skills and knowledge of agriculture. Preston’s years of outstanding work with Grow Appalachia and the recent enthusiasm of Patrick Angel, a former Pine Mountain Board member and sheep farmer, have led to new agrarian interests. The interests center on sheep and goat farming and a series of conversations have revitalized ideas around a demonstration project of sheep raising.

On August 13, 2020 a meeting was held via ZOOM to discuss the possibilities of a collaboration that would bring sheep back to Pine Mountain and would again link the agrarian past with a craft future. In attendance were Preston Jones, PMSS Executive Director, Patrick Angel, a sheep farmer and President of the Southeast Kentucky Sheep Growers Association [SEKSPA], Sarabeth Parido, a sheep farmer, wool producer, and craft workshop organizer, Ann Angel Eberhardt,co-editor of this website, and Helen Wykle, PMSS Board member and co-editor of the PMSS Archive web site.

Sheep and Malcolm Army’s grandsons, Michael and Eric with Burton Rogers, 1980s. Photo courtesy of Suzanne Arny Fullar. [pmss_archives_arny_ photo1.jpg]

UPDATE: In the Fall of 2022 sheep returned to the campus of Pine Mountain in a cooperative project with Southeast Kentucky Sheep Growers Association [SEKSPA]

The group discussed resources and options that could be exercised under COVID restrictions. Also discussed were a range of options for the types of sheep and institutional needs and the economic impact of new directions. The two options of raising sheep for meat or for wool were discussed. Both the agrarian idea and the craft focus were seen to have good instructional potential for the School as well as a revenue stream. The various programs that might be developed around a small demonstration sheep project at the School were extensive but seen to be very feasible based on models offered by PMSS and by Patrick and Sarabeth.

If there is interest in exploring this path of returning sheep to the School and building workshops around this new farm/craft direction, please contact the PMSS office and schedule time to speak with Jason Brashear, Interim Director. It is important that all interested parties explore all the options this opportunity provides.

Working with the Kentucky Sheep and Goat Development Office (KSGDO) in Frankfort and their craft consultant, Sarabeth Parido, is available to provide multiple educational workshops (small and COVID-safe) and/or virtual classes filmed at PMSS for distribution. Other options proposed in the meeting focused on the use of local and regional resources. Craft sessions were proposed as 3-5 hour sessions for very reasonable fees that would encompass a materials fee, registration fee, and cost of lodging and meals and that could be extended to seminar weekends, and other time frames, depending on COVID guidelines and enrollment. Pine Mountain is ideally suited for small groups and “distancing.” The large weaving studio at the school has 24 operational looms of variable size and a small stockpile of supplies. Examples of possible instruction workshops follow

- weaving instruction classes (based on levels)

- natural fiber workshops

- natural dye workshops

- felting workshop

- raising sheep and managing small sheep farms, how-to and hands-on

- various highly skilled artisans offering weaving and wool craft classes

- basket weaving with wool

- knitting worshops

- instruction and guidelines for establishing a small sheep-centered business

- goat cheese

- goat soap

- goat milk processing

SEE

FARM GUIDE TO SHEEP, GOATS, CRAFT, WEAVING

http://www2.ca.uky.edu/agcomm/Magazine/2013/Summer2013/story3.html The Magazine, Univ. of KY Sheep article –excellent

No Business Like Sheep Business – UK College of Agriculturewww2.ca.uky.edu › Magazine › Summer2013 › story3

https://pinemountainsettlement.net/?page_id=62470 Describes Wildflower and Bird Weekends, Summer Spinning Bee, led by local craftswoman Sarah Bailey and members of the Kentucky Weaver’s Guild. 119 attenders went through all the old-time intricate processes of shearing the sheep, carding and spinning the wool into yarn, dyeing yarn with vegetable dyes, and finally weaving the patterns. Textile Workshop. 1974-75

https://pinemountainsettlement.net/?page_id=61483 Pictures of sheep … 1970s

https://pinemountainsettlement.net/?page_id=53122 Aunt Jude Turner picture with sheep. (008) 1925

https://pinemountainsettlement.net/?page_id=52294 Shearing sheep (Shell family)

https://pinemountainsettlement.net/?page_id=48966 Alice Cobb Story of raising sheep and living off the land.

https://pinemountainsettlement.net/?page_id=48730 Florence Reeves story about Aunt Phronie .. describes her “pre delight” the care of sheep and took peace ad quiet as she carded ad spun the wool….

https://pinemountainsettlement.net/?page_id=47705 Mary Rogers subject directory: weaving of sheep wool

https://pinemountainsettlement.net/?page_id=15574 Sarah Bailey 5 entries …as she demonstrated how to shear, card, dye, and spin sheep’s wool. “THE COMMUNITY. Old friends of the School would have especially enjoyed the Spinning Bee held last summer under the direction of Mrs. Sarah Bailey, neighbor and well-known craftswoman. She and members of the Kentucky Weaver’s Guild led the 119 attendees through all the old-time intricate processes of shearing the sheep, carding and spinning the wool into yarn, dyeing the yarn with vegetable dyes, and finally weaving the patterns. It was three days out of history!” On July 13, 1935, Sarah married Frank Bailey. The couple built their own house on a small farm where they raised a variety of farm animals, including sheep which provided the wool for Sarah’s spinning, weaving and knitting. Sarah was known for her excellent cooking skills, using produce grown in her enormous garden…”

https://pinemountainsettlement.net/?page_id=41225 Aunt Nance Templeton. Great story on shearing and weaving with sheep wool….Alice Cobb as told by Pettit.

https://pinemountainsettlement.net/?page_id=41126 Uncle Wiliam raising sheep before PMSS created…

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Jul 1, 2013 – Kentucky sheep producers are tapping into a rich history. Stone Age humans domesticated sheep 10,000 years ago in Asia Minor—the first farm animals on record. They were easy to handle, and they produced meat, milk, fiber, and shelter.

GALLERY: Sheep Shots

- Sheep Sheep shed with “Lady” headed for Big Log. Photo: Helen Wykle 2018. [ P1150808-e1555820379540.jpg]

- “‘Aunt Jude’ Turner, Big Laurel, about 1925” feeding sheep. [nace_II_album_008.jpg]

- Angela Melville Album. “‘Aunt Jude’ Turner, Big Laurel, about 1925,” feeding sheep. [nace_II_album_008.jpg]

- “Aunt Jude calling her sheep.” [melv_II_album_093x.jpg]

- “‘Aunt Jude’ Turner, Big Laurel, about 1925” feeding sheep. [nace_II_album_010.jpg]

- Kingman Album. Woman surrounded by sheep. [kingman_023b]

- Kingman Album. Woman with sheep following her. [kingman_021d]

- Man with ram (sheep) at house and mail-box to right. FN Vl_35_1141

- Barn. Farm crew shearing a sheep. [II_7_barn_284.jpg]

- Medical Settlement- Big Laurel. Children, man, and sheep in snowy scene. [big_laurel_3331.jpg]

- Kingman Album. Sheep. [kingman_014a]

- Margaret Motter Album – Children playing with lambs and sheep. mott_204-.jpg

- Kingman album.”Two children holding sheep.” [kingman_014b]

- Margaret Motter Album – Children playing with sheep and lambs. mott_202-.jpg

- Kingman Album. “Two children holding sheep.” [kingman_014c]

- Selected Exhibit. Young Girl Feeding Pet Sheep Inside Home. [misc_exhibit_037.jpg]

- 0046a P. Roettinger Album.”Sheep Shearing, Uncle John Shell, Aunt Sis Shell, and Mrs. Joe Day.” [Woman standing next to a barn on left, watching man and woman sheer a sheep.]

- Aunt Sis and Uncle John [Shelll] shearing sheep. mccullough_II_077b

- 0047a P. Roettinger Album. [Aunt Sis and Mrs. Joe Day sheering a sheep, barn at left.]

- 0047b P. Roettinger Album. [Uncle John, Aunt Sis, and Mrs. Joe Day with a sheep. Woman standing next to barn at left, woman and man kneeling next to sheep.] [roe_047b.jpg]

- Sheep grazing. VII 64_life_work_007b

- Sheep grazing at PMSS, next to knoll. VII 64_life_work_006b

- Sheep grazing at PMSS. VII 64_life_work_006a

- Sheep grazing at PMSS. VII 64_life_work_006c

- Sheep grazing at PMSS. VII 64_life_work_007a

- Sheep grazing at PMSS. VII 64_life_work_007c

- Grace Rood’s jeep with girl and sheep. VI-51 – 1674.

- Aunt Sal Weaving at Pine Mountain Settlement School

- Vie of weaving room P1150211

- Natural dye striped runner. Indigo, madder, walnut, natural wool. weaving_pmss_fh_003rev2_mod

- Detail. weaving_pmss_fh_002_mod

- Weaving library

- Weaving samples P1150236

- Weaving samples P1150235

- Weaving samples P1150234

- Detail weaving_pmss_fh_003revmod3

- Detail weaving_pmss_fh_003rev2_mod2

- Detail. weaving_pmss_fh_003_mod4

- Detail. weaving_pmss_fh_002_mod6

- Variation of “Lees Surrender”? Framed on Office wall. weaving_pmss_02b_mod

- Detail weaving_pmss_02a_mod2

- Detail. weaving_pmss_01a_mod

- White wool and walnut dyed striped coverlet. weaving_pmss_01_mod

- Detail. weaving_pmss_001b_mod

- Close detail. weaving_pmss_fh_006rev_mo

- Reverse detail. weaving_pmss_fh_006rev_mod

- Detail weaving_pmss_fh_006_mod2

- Rose in the Wilderness. Similar to Fireside Industries pattern woven by Anna Ernberg, Berea. (p.38 Hall) weaving_pmss_fh_006_mod

- Detail. weaving_pmss_fh_005rev_mod

- Weaving. Coleridge School child weaving at PMSS. [picture-054.jpg]

- “Rowena Holcomb – Weaving 1948.” [nace_II_album_037.jpg]

- Woman weaving at “Old Loom.” [nace_II_album_020.jpg]

- Pine Mountain Settlement School weaving for Fireside Industries

- 053 Children with sheep. 029_V_ee_ind_set_053

- 050 Sheep in pasture with class looking on. 029_V_ee_ind_set_050.jpg]

- 052 Children feeding sheep. 029_V_ee_ind_set_052.jpg]

- 047 Two sheep being hand fed. 029_V_ee_ind_set_047.jpg]

- 046 Feeding sheep. 029_V_ee_ind_set_046.jpg]

- 042 Children and sheep. 029_V_ee_ind_set_042.jpg]

- 041 Barnyard with sheep and children. 029_V_ee_ind_set_041.jpg]

- 040 Sheep. 029_V_ee_ind_set_040.jpg]

- Sheep and Malcolm Army’s grandson with Burton Rogers, 1980s. Photo courtesy of Suzanne Arny Fullar. [pmss_archives_ arny_photo2.jpg]

- Sheep and Malcolm Army’s grandsons, Michael and Eric with Burton Rogers, 1980s. Photo courtesy of Suzanne Arny Fullar. [pmss_archives_arny_ photo1.jpg]